2. 广西科学院,广西南宁 530007

2. Guangxi Academy of Sciences, Nanning, Guangxi, 530007, China

厌氧氨氧化(Anaerobic ammonium oxidation,Anammox)脱氮工艺能直接以亚硝酸盐为电子受体实现氨氮向氮气的转化。与传统的硝化和反硝化工艺相比,Anammox脱氮工艺无需有机碳源,无需曝气,能减少90%的温室气体排放以及降低90%的污泥产量[1],已广泛应用于污泥厌氧消化液、禽畜养殖废水等高氨氮废水处理领域[2, 3]。然而在实际应用中,Anammox脱氮工艺进水中NO2-/NH4+比值需要严格控制在1.32附近,过高或过低都会导致出水中亚硝酸盐和氨氮的积累[4, 5]。此外,Anammox脱氮时会将亚硝酸盐转化为硝酸盐,使其理论脱氮效率最高能达到89%,但因进水限制实际应用中仅能达到70%左右,而且厌氧出水中常含有过饱和的甲烷,甲烷释放到大气中无疑增加了废水处理过程中的碳排放[6]。随着反硝化型厌氧甲烷氧化(Denitrifying Anaerobic Methane Oxidation,DAMO)微生物的发现,能够同时利用甲烷、硝态氮和亚硝态氮的DAMO脱氮工艺被成功建立,该工艺能够以甲烷为电子供体,硝态氮为电子受体,实现同步除甲烷和脱氮[4]。DAMO和Anammox的耦合(DAMO-Anammox)工艺将甲烷减排与低能耗高效脱氮相结合,在我国提倡氮污染控制及碳中和的背景下,其在可持续型污水处理领域有广阔的应用前景。然而,该脱氮工艺所需要的3种主要功能微生物均为自养菌,其倍增时间与生长代谢速率均十分缓慢,且易受废水中溶解氧、溶解甲烷与亚硝酸盐浓度的影响。微生物之间的协同与竞争作用也使得DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺比起单一脱氮工艺更复杂,启动与稳定运行难度更大。因此,这种能够利用甲烷同步去除氨氮、硝态氮和亚硝态氮的“理想协同工艺”从理论到应用仍需要深入研究。

本文主要概述DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺过程及微生物的协同与竞争机制,不同电子受体的类型对DAMO-Anammox微生物胞外电子传递机制及脱氮除甲烷效率的影响。此外,本文还探讨了DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺在大规模应用中主要面临的挑战并结合相关研究提出可能的突破方向。

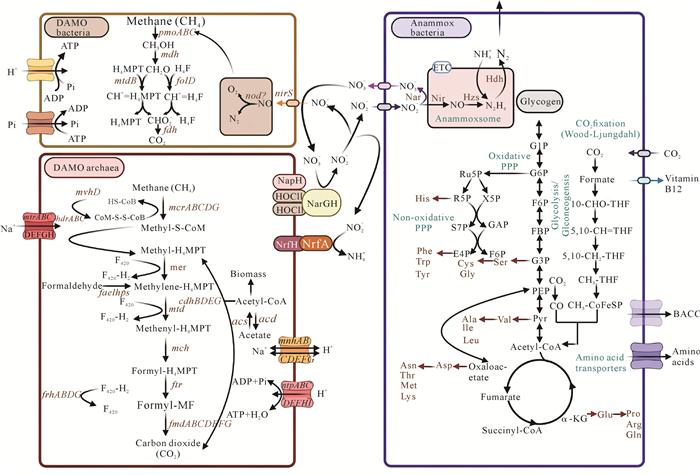

1 DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺过程及其微生物的协同与竞争机制 1.1 DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺反应机理DAMO和Anammox微生物广泛而丰富,在各种环境中都有检出,如河床、湿地、淡水沉积物、水稻土、泥炭地、污水处理厂、海洋沉积物、湖泊、森林等[7-9]。在实验室规模上,它们成功地共存于单一的生物反应器中[10],进一步证明了它们在多来源的大规模废水处理中的潜力。DAMO-Anammox过程主要由3种功能微生物协同完成,其中以Candidatus Methanoperedens nitroreducens为代表的DAMO古菌以硝酸盐作为电子受体,甲烷作为电子供体,反应生成CO2和亚硝酸盐[11, 12];以Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera为代表的DAMO细菌以甲烷作为电子供体,将亚硝酸盐还原为N2和CO2;而归为浮霉菌门的Anammox细菌,在无需额外碳源的条件下,通过细胞内特有的厌氧氨氧化体直接利用氨氮和亚硝态氮[13]。

DAMO-Anammox一体化脱氮工艺过程和氮循环的相关代谢途径如图 1所示。DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺过程有3个主要反应方程式:DAMO古菌反应(1),DAMO细菌反应(2),Anammox细菌反应(3)。

| $ \begin{array}{l} \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;2 \mathrm{CH}_4+8 \mathrm{NO}_3^{-} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{CO}_2+8 \mathrm{NO}_2^{-}+4 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \\ \left(\Delta \mathrm{G}^0=-523 \mathrm{~kJ} \cdot \mathrm{mol}^{-1} \mathrm{N}_2\right), \end{array} $ | (1) |

| $ \begin{array}{l} \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;3 \mathrm{CH}_4+8 \mathrm{NO}_2^{-}+8 \mathrm{H}^{+} \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{CO}_2+4 \mathrm{N}_2+10 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \\ \left(\Delta \mathrm{G}^0=-928 \mathrm{~kJ} \cdot \mathrm{mol}^{-1} \mathrm{~N}_2\right), \end{array} $ | (2) |

| $ \begin{array}{l} \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\mathrm{NH}_4^{+}+\mathrm{NO}_2^{-} \rightarrow \mathrm{N}_2+2 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}\left(\Delta \mathrm{G}^0=-357 \mathrm{~kJ} \cdot\right. \\ \left.\mathrm{mol}^{-1} \mathrm{~N}_2\right) \text { 。} \end{array} $ | (3) |

在Anammox细菌中,大部分亚硝酸盐首先被亚硝酸盐还原酶(Nir)还原为一氧化氮(NO),然后NO作为终端电子受体通过联氨合酶(Hzs)将铵氧化成肼(N2H4),最后在肼脱氢酶(Hdh)作用下生成N2并获得能量[15, 16]。Anammox细菌还会将一部分亚硝酸盐氧化为硝酸盐并获得生长的能量,但硝酸盐本身并不能被自身代谢。在DAMO古菌中,甲烷可以被甲基-CoM还原酶活化,并且随后经由反向产甲烷作用完全氧化成CO2,产生的电子转移到细胞质电子载体,随后通过一系列电子传递蛋白传递到细胞的假周质空间中,外部电子受体硝酸盐被硝酸盐还原酶(Nar)还原为亚硝酸盐[17, 18]。在DAMO过程中部分亚硝酸盐被产铵型亚硝酸还原酶转化为铵盐,而在DAMO古菌的两个还原过程中亚硝酸盐是主要产物(90%)且高于铵盐的产生速率[19]。DAMO细菌由于其独特的内部好氧途径,能利用亚硝酸还原酶(NirS)将亚硝酸盐转化为NO,继而产生O2和N2,减少具有潜在毒性的亚硝酸盐的积累[17, 20]。

DAMO-Anammox一体化脱氮工艺集合了两种工艺的优点,弥补了单一脱氮工艺的不足:①能够扩大Anammox过程中严格要求的NO2-/NH4+比值范围,从而提高脱氮工艺的适用性,对主流的废水有良好的脱氮效率[21]。② DAMO古菌能够利用Anammox细菌产生的硝酸盐,在处理低总氮浓度(< 8 mg·L-1)的废水时可实现完全脱氮,而且因为过量的亚硝酸盐又被DAMO细菌去除,所以处理过程中几乎不释放N2O[20, 22]。③理论上,一体化脱氮工艺在不曝气的情况下能减少15%左右的甲烷排放,并节省曝气的能量消耗[23]。④大规模的污水处理厂应用DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺可在实现更高的能量回收的同时使出水中氮浓度达到排放标准,在脱氮技术中表现出巨大的发展潜力[10]。

1.2 DAMO-Anammox微生物的协同与竞争机制DAMO和Anammox微生物由于利用共同的底物亚硝酸盐,当它们处于同一环境时存在两种潜在的竞争关系:① DAMO古菌和DAMO细菌竞争水中的溶解态CH4。② DAMO细菌和Anammox细菌竞争亚硝酸盐底物。在硝酸盐和铵盐底物下,硝酸盐首先被DAMO古菌还原为亚硝酸盐,随后与DAMO细菌竞争甲烷。与此同时,DAMO细菌与Anammox细菌竞争亚硝酸盐,DAMO古菌占据主导地位[11]。在亚硝酸盐和铵盐底物下,Anammox细菌首先将亚硝酸盐转化为N2和硝酸盐,随后DAMO古菌进一步还原硝酸盐,Anammox细菌占主导地位。亚硝酸盐和铵盐的产生使得DAMO古菌更适合作为Anammox细菌的合作伙伴。而DAMO细菌则还原Anammox余下的和DAMO古菌产生的亚硝酸盐,缓解亚硝酸盐的积累带来的潜在毒性,其生长在一定程度上依赖DAMO古菌和Anammox细菌[24, 25]。此外,微生物间对底物的亲和力也是影响其丰度的关键,DAMO古菌对甲烷的亲和力高于DAMO细菌[26],而Anammox细菌对亚硝酸盐的亲和力为DAMO细菌的5倍以上[27]。DAMO-Anammox过程中的微生物群落相对丰度随着进水中底物的变化而发生改变,微生物群落的动态变化是微生物间相互竞争作用的直接反映。

DAMO和Anammox微生物之间竞争的直接结果是不同系统中的空间分布和氮去除性能的差异。对于附着生物系统而言,微生物附着在固体表面形成层状生物膜,其中的功能微生物丰度取决于环境与操作条件[24]。在颗粒系统中,DAMO微生物和Anammox细菌可能均匀分布在颗粒中,或者DAMO微生物位于颗粒的内部层,而Anammox细菌形成外部包覆层,这取决于不同底物的可利用性(氧气、硝酸盐、氨氮等的浓度)[22]。

2 DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺中潜在的电子受体与电子传递机制 2.1 潜在电子受体生物体内持续发生着快速的电子和质子传递过程,电子传递过程对于互营氧微生物来说非常重要。所有微生物的能量摄取都来自有机或无机化合物氧化耦合外部电子受体的还原过程。在大多数微生物中,能量摄取通过使用可溶性电子受体和供体来实现是可能的。DAMO和Anammox微生物生长在严格厌氧的环境中,以硝酸盐和亚硝酸盐为电子受体,然而,厌氧条件下污水中缺乏电子受体限制了该工艺的应用。根据最新的研究发现,DAMO和Anammox微生物都具有胞外传递电子的能力,可以将甲烷氧化产生的电子和铵盐中的电子转移到胞外的电子受体上[11, 28]。DAMO古菌直接将电子传输到细胞外空间以还原铁或锰固体氧化物,乙酸盐和其他可扩散介体充当电子载体以实现由DAMO驱动的协同胞外电子传递过程[28, 29]。此外,添加一些电子传递介体(如腐殖质[30]、醌类化合物、金属氧化物[31]等)或通过耦合自养反硝化均有助于提高DAMO和Anammox微生物的脱氮除甲烷性能。一些学者还研究了甲烷驱动的微生物燃料电池(Microbial Fuel Cell,MFC),DAMO古菌以电极作为电子受体,通过涉及生化途径的电化学反应将化学能转化为电能,并同时实现脱氮[32]。在Anammox过程中,亚硝酸盐不是唯一的电子受体,Anammox微生物还可以使用多种形式的多种物质(如一氧化氮[33]、铁盐[34]、硫酸盐[35],甚至微生物电解池电极等)充当电子传递链中的电子受体。

2.1.1 铁盐铁是生物系统中最丰富的过渡金属,被用作氧化还原化学、电子转移反应和调节过程中的必需辅因子。铁能与碳、氧、硫和氮反应形成络合物,并且具有广泛的氧化还原电位范围(-700 mV至+350 mV),这些特性使其参与了大部分生物地球化学循环[36]。Anammox微生物的能量代谢依赖于3类含铁辅因子,即血红素C、铁硫簇和铁镍蛋白,这些辅因子确保了质子动力的产生,维持能量转换方面的基本生命活动,并作为支撑维持Anammox细菌中凝聚层的形态结构[37]。氨氧化体中大量的铁结合蛋白也是导致Anammox细菌的富集培养物常呈现出鲜红色的原因[38]。许多研究发现铁可作为甲烷厌氧氧化的电子受体之一,DAMO古菌可能通过C型细胞色素间接地将电子传递给Fe3+矿物[39]。Chang等[40]研究发现,在DAMO工艺中添加纳米Fe3O4颗粒会增强亚硝酸盐的还原速率,约为不添加任何添加剂的对照的1.6倍。然而,还需要进一步的研究来评估在主流废水处理工艺中添加铁以提高甲烷和氮去除率的有效性,以及硫化物控制和除磷等其他益处。

2.1.2 硫酸盐硫和氮的循环通常交织在一起,并在广泛的生物环境中普遍存在。硫酸盐还原氨氧化在厌氧条件下以废水中固有的硫酸盐为电子受体,将氨态氮氧化为氮气,无需额外添加有机物,也不产生二次污染,这一现象首次在2001年被确定[41]。类似于亚硝酸盐,硫酸盐是硫的最高价态的化合物,其可以稳定地大量存在于水中并且在Anammox反应中用作均相电子受体。一般来说,硫化物对生物体有负面影响,硫酸盐也会抑制微生物的活性,甚至使蛋白质变性。但实际上,在适宜Anammox细菌生存的高pH值环境下,硫酸盐对Anammox过程的抑制作用会减弱[42]。Liu等[43]使用硫酸盐取代亚硝酸盐,在Anammox过程中成功实现以硫酸盐为唯一电子受体的脱氮过程,硫化硫酸盐也被证实参与了反硝化和Anammox耦合脱氮工艺[44]。

2.1.3 电极微生物电化学系统(Microbial Electrolysis System, MES)能够将电化学反应与生物代谢过程结合起来,系统内微生物进行的细胞外电子转移构成了该系统的主要驱动力。在MES中,电活性微生物能够将代谢过程产生的电子转移到固态电极或从固态电极转移电子并形成电路[45]。在DAMO和Anammox的MES中,典型的电极材料包括Fe[46]、石墨烯[47]、碳毡[48]等。工作电极作为电子受体来氧化铵,铵盐和亚硝酸盐分别作为Anammox过程流入底物中的主要电子供体和受体。因此,两种主要给水基质的阳极和阴极之间的电势差可以用作自发反应的催化剂[49]。在缺少阳极和阴极电位差的MES中,非自发反应可以通过外部电压来支持并加速自发反应。通常,Anammox-MES根据电压和形式在阳极处产生不同的产物。例如,在单室电解池的Anammox过程中,在0.5 V电压下产生亚硝酸盐;在双室电解池的Anammox过程中,阳极电极用作电子受体,消耗的铵约95%用于产生硝酸盐[50, 51]。DAMO微生物也被证实可以将甲烷氧化和反硝化耦合过程中产生的电子转移到电极上,使用辅助电压能进一步增强DAMO的甲烷氧化和反硝化作用[52, 53]。

电极驱动的DAMO-Anammox过程具有巨大的潜力,因为它与微生物胞外电子传递机制相似,并得到广泛认可。尽管存在一些限制,但使用电极作为电子受体具有许多优点。首先,它无需额外添加亚硝酸盐,从而显著降低了成本;其次,通过利用可再生能源如太阳能或风能来驱动电极,使得这种方法成为替代其他电子受体的环境友好方案;最后,电极能够提供稳定和可调节的电子流,从而实现对反应速率的精确控制。以上都是DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺能够利用多种不同电子受体促进其过程的证明,然而,不同的电子受体对DAMO-Anammox过程中的脱氮速率的影响也不同,确切的机制有待进一步研究。

2.2 电子传递机制DAMO-Anammox微生物的电子传递在脱氮过程中具有重要作用。在胞内电子转移过程中,DAMO微生物将甲烷氧化为甲酸并通过胞内电子传递链将产生的电子传递给细胞膜上的细胞色素[12]。Anammox微生物的电子在Anammox体中产生,并依赖一系列蛋白电子传递链传递到Anammox体膜上;然后,微生物使用还原物质沿着细胞电子呼吸链将电子传递到细胞外电子受体中,产生质子梯度用于合成ATP并提供能量[54, 55]。而这两种微生物的胞外电子传递能否链接这两个生物过程,并通过电子交流实现两者之间的协同作用还有待研究。总之,提高电子受体和电子供体之间的电子交换和利用效率,是打破废水中缺乏电子受体的限制瓶颈和提高废水中氮通量转化速率的关键。

在DAMO微生物中,一个甲烷氧化的电子代谢途径模型为逆向甲烷生成产生F420-H2、硫醇辅因子CoM-SH和CoB-SH以及还原的铁氧化还原蛋白(Fdred)[56, 57]。F420-H2可被脱氢酶(Fqo)氧化,电子转移到甲基萘醌,随后杂二硫还原酶(Hdr)反应被逆转,在生成杂二硫(CoM-S-S-CoB)的同时甲基萘醌被还原为甲基萘醇[58]。甲基萘醇可被细胞色素b复合物氧化,氧化产生的电子通过可溶性细胞色素c传递至硝酸盐还原酶(Nar)复合物,将硝酸盐还原为亚硝酸盐[59];使用甲基萘醇作为电子供体,亚硝酸盐还原酶(Nrf)将部分亚硝酸盐进一步还原为铵盐。在Anammox微生物中,通常通过多种酶(如Nir、Nar、HAO、HDH等)催化氧化还原反应产生电子。高能电子通过糖代谢副产物NADH传递到蛋白质复合物,在这些复合物中电子通过多个氧化还原中心转移。由于不同氧化还原中心对电子的亲和力存在差异,电子在各种蛋白质复合物(包括酶)之间传递。为了与必需的酶建立联系,电子必须穿过厌氧氨细菌的细胞壁、细胞质膜、胞质内膜和厌氧氨酶体膜,所以Anammox细菌中一般含有多种由一系列蛋白质和电子载体组成的跨膜电子传递系统[60, 61]。

在细胞外电子转移中,微生物利用还原性物质将电子沿电子传递链转移至细胞外电子受体,为微生物代谢提供能量。由于细胞外电子传递与细胞内电子传递不同,它更多地依赖于自由基或导电介质,而不仅仅依赖于导电蛋白质。为了利用外部更宽范围的电子受体,DAMO和Anammox微生物会分泌微小分子(如黄素、蒽醌等[62])和导电蛋白[63]作为电子穿梭体来帮助膜导电蛋白将电子转移到胞外电子受体。胞外聚合物中的蛋白质、导电DNA、官能团、腐殖质等电化学物质都被证实具有可以用作胞外电子转移介质的潜力[64, 65]。根据最新的报道,DAMO古菌还有通过合成“纳米导线”远距离将电子直接传递到胞外电子受体的潜力[66]。氧化还原介质在微生物的胞外电子传递中也起到重要的促进作用,它们通过接受或提供电子的方式,参与微生物代谢过程中的氧化还原反应,氧化还原介质的存在可以增强微生物的电子传递效率,促进微生物的代谢活性。这些电子中介体的加入提供了额外的电子传递路径,在缺乏良好的固体电子受体或跨膜电子传递难度较大的环境条件下,提高了微生物的电子传递效率[67]。

3 DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺应用的限制因素及改进策略 3.1 DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺应用的限制因素 3.1.1 微生物生长速率低DAMO和Anammox微生物都属于厌氧自养菌,需要严格的底物供给和环境条件,在细胞内代谢过程中具有复杂性和独特性,这大大限制了它们的生长速率,倍增时间通常达到2周甚至数月,使其人工培养和富集成为一个巨大的挑战[68, 69]。此外,一方面,DAMO细菌的活性显著低于其他甲烷氧化菌,这一现象可能是由于DAMO细菌中能够催化甲烷氧化的甲烷单加氧酶(particulate Methane Monooxygenase, pMMO)在细胞膜上数量较少,而其他甲烷氧化菌则拥有丰富的内膜结构,可以用来附着大量的pMMO[70]。另一方面,DAMO细菌利用耗能极高的卡尔文循环来同化二氧化碳,而不像其他细菌那样采用更节能的5-磷酸核酮糖途径进行合成代谢。由于其能源获取较为缓慢且消耗较多,这可能是导致DAMO微生物生长缓慢的重要原因[71]。据报道,DAMO和Anammmox微生物的最佳生长温度为30-35 ℃,pH值为7.0-8.0,尽管它们的生长温度和pH值范围较宽,但pH值的波动会导致对微生物具有细胞毒性的亚硝酸或游离氨的形成[72]。

3.1.2 甲烷气液传质效率低目前,实验室规模的DAMO微生物通常是通过通入纯甲烷和二氧化碳气体进行富集,这不仅消耗额外的能量,还会导致未被利用的甲烷被释放到大气中,增加温室气体排放。一方面,在实际污水处理中,由于甲烷在水中的溶解度低(在1个大气压下为22 mg CH4·L-1)[73],且会不断扩散到空气中,所以甲烷在液相中的浓度也是限制DAMO微生物生长的主要原因之一。另一方面,DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺的脱氮速率远大于甲烷氧化的速率,报道的DAMO细菌甲烷代谢速率仅为0.09×10-15-0.30×10-15 mol CH4(per cell)[74],在实际应用中,消耗完水中全部溶解态甲烷需要的水力停留时间长,跟不上总氮的去除速度,导致20%-60%的溶解态甲烷重新释放回大气中。甲烷分压对DAMO微生物的脱氮性能具有重要影响。一项研究发现,当甲烷分压从0.24个大气压升至1.39个大气压时,DAMO古菌和DAMO细菌的活性分别增加58%和283%[75], 这表明甲烷分压可以被视为一种潜在的可调节变量,可用来控制DAMO反应的速率。因此,需要研究新的技术策略以在DAMO微生物的培养中提高甲烷的气液传质效率与利用率。

3.1.3 脱氮性能比主流工艺低根据目前的研究报道,DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺的脱氮速率为12-684 mg N·L-1·d-1,而主流以曝气加额外碳源进行的异养反硝化工艺脱氮速率最高可达到3 g N·L-1·d-1[76-78],相比之下还存在较大差距。从工程应用的角度来看,总氮去除负荷通常需要满足1 kg N·m-3·d-1以上才能具备应用价值,这个要求对于DAMO和Anammox过程都是一个巨大的挑战。在DAMO-Anammox系统中,主流的最佳脱氮速率为280 mg N·L-1·d-1,去除原水中50 mg·L-1的氮负荷所需的水力停留时间(Hydraulic Retention Time, HRT)约为4.3 h[21]。这表明需要非常大的反应器体积才能满足大量废水的脱氮需求,因此需要很高的资金和运行成本。综上,优化DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺对于提高甲烷和总氮的去除率具有重要意义。

3.2 DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺应用的改进策略 3.2.1 新型反应器构型脱氮生物反应器的设计主要考虑的因素是脱氮微生物生物量的保留和底物的供给与传质。相比于序批式反应器和连续搅拌混合反应器,膜生物反应器(Membrane Bioreactor, MBR)和膜曝气生物反应器(Menbrane Aeration Bioreactor, MABR)中形成的生物膜拥有比悬浮生长系统更高的氮和甲烷负荷率、气体传递效率和利用效率,因此更适合DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺。在MABR中,气体基质在曝气膜的作用下以微小或无气泡形式进入液体,附着在曝气膜表面的生物膜能够高效地利用曝气膜提供的气态基质和培养基提供的液态基质,有效提高了甲烷气体的利用率[79]。由于DAMO和Anammox微生物的倍增时间长,通过膜曝气形成的生物膜也能有效截留微生物,以维持较高的微生物浓度[80]。且液体扩散层位于生物膜的外层,DAMO微生物能够最大限度地利用甲烷(90%以上),防止气体向液体扩散流失[81]。有研究报道,MBR特别适用于DAMO-Anammox工艺,在主流废水和侧流废水中均获得了较高的脱氮速率,分别为0.28 kg N·m-3·d-1和1.03 kg N·m-3·d-1 [21]。

然而,随着反应时间的延长和生物膜厚度的增加,DAMO古菌从液相中获得硝酸盐的能力将受到更大的限制,这是由于生物膜中电子供体和受体的反扩散效应造成的[82]。此外,生物膜中DAMO和Anammox微生物的空间分布可能导致DAMO古菌活性难以进一步提高,从而影响脱氮效果[83]。此外,在长期运行的膜生物反应器中超滤膜和渗透膜经常会发生膜污染,严重降低甲烷通量和底物扩散率[27, 84]。膜污染的主要原因是生物膜中胞外聚合物积累阻碍了传质,如何清理胞外聚合物净化生物膜,延长膜的使用寿命,值得进一步研究[85]。

考虑到MBR和MABR的投资和运行成本较高,驯化颗粒污泥可能提供了一种新的替代方案。Fan等[86]通过一种装有气体渗透膜组件的新型颗粒升流反应器,成功获得富集了高丰度DAMO和Anammox微生物的颗粒污泥,该颗粒污泥形成了一种高密度聚集的层状结构,外层为Anammox微生物,内部为DAMO菌,脱氮速率可分别达到1.08 g NO3-·L-1·d-1和0.81 g NH4+·L-1·d-1。DAMO-Anammox颗粒污泥还提供了良好的沉降性能和生物量保留效果,减少了生物质的流失[87]。

3.2.2 提高微生物生长速率及代谢活性根据以往关于DAMO和Anammox微生物富集的报道中,温度在35 ℃左右,pH值为7.0-7.5时,富集培养物的活性最高[86, 88]。关键酶的浓度决定了微生物的活性,甲基辅酶M还原酶(Mcr)和pMMO是DAMO微生物的关键酶,Hzs和Hdh是Anammox细菌的关键酶,而C型细胞色素蛋白是两者所必需的。Mcr和pMMO通过断裂甲烷的C-H键来活化甲烷,Hzs被用于产生肼作为最终能量来源,并向Hdh提供电子,催化形成N-N键并连接能量生成过程,其中C型细胞色素等导电蛋白用于传递电子[89, 90]。人工添加一些微量金属元素如Cu、Fe、Ni等,能够促进上述关键酶的表达。Hatamoto等[91]通过添加浓度为6 μmol·L-1的Cu,提高了DAMO细菌pMMO的表达,促进了反硝化过程。Lu等[92]研究了最适的Fe添加浓度,发现Anammox细菌、DAMO古菌和DAMO细菌在短期内的最佳Fe浓度分别为80、20和80 μmol·L-1,随着Fe的添加,铵和硝酸盐的去除率分别增加了13.6和9.2倍。DAMO和Anammox微生物属于专性厌氧菌,其生长需要低氧化还原电位(Oxidation Reduction Potential, ORP)环境,而通过添加零价Fe等还原性金属可以创造更稳定的还原环境,从而促进这些微生物的正常生长和代谢[46]。

3.2.3 电化学辅助强化外加电场可以通过不同的机制促进DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺过程,对微生物进行电处理可以增加膜的通透性和ATP含量,提高微生物活性[93]。电极充当了外部的电子受体和供体,如DAMO和Anammox分泌的类似血红素的穿梭电子中介体能够与电极进行电子交换,促进了微生物的胞外电子传递过程[94]。一般而言,甲烷等电子供体氧化产生的电子用于电子受体(亚硝酸盐)的还原,形成电子回路。当微生物从电极上获取额外的电子时,可以加速电子流并增强代谢,Yin等[95]证明了使用1 V的电压能够促进DAMO过程中亚硝酸盐和甲烷的消耗。同时电刺激能够对污水中混合体系的微生物起到富集和驯化作用,从而改变群落结构,使其进一步富集DAMO和Anammox微生物,提高系统的脱氮效率。此外,电极能够提供稳定和可调节的电子流,从而实现对反应速率的精确控制。

4 展望DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺将两个独立的脱氮工艺联系起来,不同的反硝化型甲烷氧化菌可以利用硝酸盐、甲烷作为电子供体产生亚硝酸盐和铵盐,与Anammox过程形成互补实现耦合脱氮。利用温室气体甲烷作为电子供体,不仅能在消耗温室气体甲烷的同时有效解决污水脱氮中碳源不足的问题,而且能提高出水的脱氮效果,实现完全脱氮,这在生物脱氮领域极具应用价值。

针对DAMO-Anammox脱氮工艺存在的功能微生物生长速率慢、富集时间长、气液传质效率低、脱氮效率低、场合受限等问题,今后的研究可以从以下方面考虑:①通过现代微生物技术获取纯培养的DAMO和Anammox微生物,进一步通过基因工程改进微生物的生长代谢活性,或者引入高反应速率的异养微生物以构建高效的脱氮菌群。②利用材料学的方法开发对甲烷有高吸附性的材料,使DAMO微生物能够更好地利用甲烷;采用微生物固定化技术,强化水中碳、氮源与微生物的接触,提高传质效率。③通过其他先进的水处理技术,如高级氧化技术、膜分离技术、生物电化学技术、催化剂辅助降解技术等,与污水脱氮工艺相结合,提高脱氮的效率及污水的适用范围。④目前该耦合工艺多处于实验室规模的探索研究阶段,在实现大规模的应用前,还需要进一步利用分子生物学与合成生物学等手段阐明相关微生物的代谢途径及互作机理,以及开展相关工艺的优化研究。

| [1] |

ALI M, OKABE S. Anammox-based technologies for nitrogen removal: advances in process start-up and remaining issues[J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 141: 144-153. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.06.094 |

| [2] |

YANG Y C, LI M, HU Z, et al. Deep insights into the green nitrogen removal by anammox in four full-scale WWTPs treating landfill leachate based on 16S rRNA gene and transcripts by 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 276: 124176. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124176 |

| [3] |

KANG D, XU D D, YU T, et al. Texture of anammox sludge bed: composition feature, visual characterization and formation mechanism[J]. Water Research, 2019, 154: 180-188. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2019.01.052 |

| [4] |

XIE G J, CAI C, HU S H, et al. Complete nitrogen removal from synthetic anaerobic sludge digestion liquor through integrating anammox and denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation in a membrane biofilm reactor[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(2): 819-827. |

| [5] |

LAURENI M, FALÅS P, ROBIN O, et al. Mainstream partial nitritation and anammox: long-term process stability and effluent quality at low temperatures[J]. Water Research, 2016, 101: 628-639. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.005 |

| [6] |

LOTTI T, KLEEREBEZEM R, HU Z, et al. Simultaneous partial nitritation and anammox at low temperature with granular sludge[J]. Water Research, 2014, 66: 111-121. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2014.07.047 |

| [7] |

CHEN J, ZHOU Z C, GU J D. Complex community of nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation bacteria in coastal sediments of the Mai Po wetland by PCR amplification of both 16S rRNA and pmoA genes[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99(3): 1463-1473. DOI:10.1007/s00253-014-6051-6 |

| [8] |

MARTINEZ-CRUZ K, SEPULVEDA-JAUREGUI A, CASPER P, et al. Ubiquitous and significant anaerobic oxidation of methane in freshwater lake sediments[J]. Water Research, 2018, 144: 332-340. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2018.07.053 |

| [9] |

SHEN L D, OUYANG L, ZHU Y Z, et al. Active pathways of anaerobic methane oxidation across contrasting riverbeds[J]. The ISME Journal, 2019, 13(3): 752-766. DOI:10.1038/s41396-018-0302-y |

| [10] |

LIU T, HU S H, GUO J H. Enhancing mainstream nitrogen removal by employing nitrate/nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation processes[J]. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 2019, 39(5): 732-745. DOI:10.1080/07388551.2019.1598333 |

| [11] |

NIE W B, DING J, XIE G J, et al. Simultaneous nitrate and sulfate dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane linking carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycles[J]. Water Research, 2021, 194: 116928. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2021.116928 |

| [12] |

LIU T, HU S H, YUAN Z G, et al. Simultaneous dissolved methane and nitrogen removal from low-strength wastewater using anaerobic granule-based sequencing batch reactor[J]. Water Research, 2023, 242: 120194. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2023.120194 |

| [13] |

LAWSON C E, WU S, BHATTACHARJEE A S, et al. Metabolic network analysis reveals microbial community interactions in anammox granules[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8(1): 15416. DOI:10.1038/ncomms15416 |

| [14] |

CHEN Y, JIANG G M, SIVAKUMAR M, et al. Enhancing integrated denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation and anammox processes for nitrogen and methane removal: a review[J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2023, 53(3): 390-415. DOI:10.1080/10643389.2022.2056391 |

| [15] |

KARTAL B, MAALCKE W J, DE ALMEIDA N M, et al. Molecular mechanism of anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. Nature, 2011, 479(7371): 127-130. DOI:10.1038/nature10453 |

| [16] |

KARTAL B, DE ALMEIDA N M, MAALCKE W J, et al. How to make a living from anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2013, 37(3): 428-461. DOI:10.1111/1574-6976.12014 |

| [17] |

HAROON M F, HU S H, SHI Y, et al. Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to nitrate reduction in a novel archaeal lineage[J]. Nature, 2013, 500(7464): 567-570. DOI:10.1038/nature12375 |

| [18] |

ARSHAD A, SPETH D R, DE GRAAF R M, et al. A metagenomics-based metabolic model of nitrate-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane by Methanoperedens-like archaea[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6(273): 1423. |

| [19] |

ETTWIG K F, ZHU B, SPETH D, et al. Archaea catalyze iron-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016, 113(45): 12792-12796. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1609534113 |

| [20] |

ETTWIG K F, BUTLER M K, PASLIER D L, et al. Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7288): 543-548. DOI:10.1038/nature08883 |

| [21] |

XIE G J, LIU T, CAI C, et al. Achieving high-level nitrogen removal in mainstream by coupling anammox with denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation in a membrane biofilm reactor[J]. Water Research, 2018, 131: 196-204. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2017.12.037 |

| [22] |

FAN S Q, XIE G J, LU Y, et al. Granular sludge coupling nitrate/nitrite dependent anaerobic methane oxidation with anammox: from proof-of-concept to high rate nitrogen removal[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(1): 297-305. |

| [23] |

VAN KESSEL M A, STULTIENS K, SLEGERS M F, et al. Current perspectives on the application of N-damo and anammox in wastewater treatment[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2018, 50: 222-227. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2018.01.031 |

| [24] |

FU L, DING J, LU Y Z, et al. Hollow fiber membrane bioreactor affects microbial community and morphology of the DAMO and Anammox co-culture system[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 232: 247-253. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.02.048 |

| [25] |

NIE W B, DING J, XIE G J, et al. Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled with dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium fuels anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(2): 1197-1208. |

| [26] |

HE Z F, CAI C, GENG S, et al. Modelling a nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation process: parameters identification and model evaluation[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2013, 147: 315-320. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.001 |

| [27] |

PENG L, NIE W B, DING J, et al. Denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation and anammox process in a membrane aerated membrane bioreactor: kinetic evaluation and optimization[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(11): 6968-6977. |

| [28] |

SHAW D R, ALI M, KATURI K P, et al. Extracellular electron transfer-dependent anaerobic oxidation of ammonium by anammox bacteria[J]. Nature Communications, 2020, 11(1): 2058. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-16016-y |

| [29] |

SCHELLER S, YU H, CHADWICK G L, et al. Artificial electron acceptors decouple archaeal methane oxidation from sulfate reduction[J]. Science, 2016, 351(6274): 703-707. DOI:10.1126/science.aad7154 |

| [30] |

VALENZUELA E I, AVENDAÑO K A, BALAGURUSAMY N, et al. Electron shuttling mediated by humic substances fuels anaerobic methane oxidation and carbon burial in wetland sediments[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 650: 2674-2684. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.388 |

| [31] |

YANG L L, LI W X, ZHU H J, et al. Functions and mechanisms of sponge iron-mediated multiple metabolic processes in anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2023, 390: 129821. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129821 |

| [32] |

PALANISAMY G, JUNG H Y, SADHASIVAM T, et al. A comprehensive review on microbial fuel cell technologies: processes, utilization, and advanced developments in electrodes and membranes[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 221: 598-621. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.172 |

| [33] |

HU Z Y, WESSELS H J C T, VAN ALEN T, et al. Nitric oxide-dependent anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. Nature Communications, 2019, 10(1): 1244. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-09268-w |

| [34] |

YANG W H, WEBER K A, SILVER W L, et al. Nitrogen loss from soil through anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to iron reduction[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2012, 5(8): 538-541. DOI:10.1038/ngeo1530 |

| [35] |

WANG Q, ROGERS M J, NG S S, et al. Fixed nitrogen removal mechanisms associated with sulfur cycling in tropical wetlands[J]. Water Research, 2021, 189: 116619. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2020.116619 |

| [36] |

LIU J, CHAKRABORTY S, HOSSEINZADEH P, et al. Metalloproteins containing cytochrome, iron-sulfur, or copper redox centers[J]. Chemical Reviews, 2014, 114(8): 4366-4469. DOI:10.1021/cr400479b |

| [37] |

QIAN G S, HU X M, LI L, et al. Effect of iron ions and electric field on nitrification process in the periodic reversal bio-electrocoagulation system[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 244: 382-390. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.155 |

| [38] |

FEROUSI C, LINDHOUD S, BAYMANN F, et al. Iron assimilation and utilization in anaerobic ammonium oxidizing bacteria[J]. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 2017, 37: 129-136. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.03.009 |

| [39] |

LEU A O, CAI C, MCILROY S J, et al. Anaerobic methane oxidation coupled to manganese reduction by members of the Methanoperedenaceae[J]. The ISME Journal, 2020, 14(4): 1030-1041. DOI:10.1038/s41396-020-0590-x |

| [40] |

CHANG J L, WU Q, YAN X X, et al. Enhancement of nitrite reduction and enrichment of Methylomonas via conductive materials in a nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation system[J]. Environmental Research, 2021, 193: 110565. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2020.110565 |

| [41] |

FDZ-POLANCO F, FDZ-POLANCO M, FERNANDEZ N, et al. New process for simultaneous removal of nitrogen and sulphur under anaerobic conditions[J]. Water Research, 2001, 35(4): 1111-1114. DOI:10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00474-7 |

| [42] |

WISNIEWSKI K, DI BIASE A, MUNZ G, et al. Kinetic characterization of hydrogen sulfide inhibition of suspended anammox biomass from a membrane bioreactor[J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2019, 143: 48-57. DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2018.12.015 |

| [43] |

LIU S T, YANG F L, GONG Z, et al. Application of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing consortium to achieve completely autotrophic ammonium and sulfate removal[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2008, 99(15): 6817-6825. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.054 |

| [44] |

LIU Z H, LIN W M, LUO Q J, et al. Effects of an organic carbon source on the coupling of sulfur(thiosulfate)-driven denitration with Anammox process[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2021, 335: 125280. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125280 |

| [45] |

HYUN CHUNG T, MESHREF M N A, RANJAN DHAR B. A review and roadmap for developing microbial electrochemical cell-based biosensors for recalcitrant environmental contaminants, emphasis on aromatic compounds[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 424: 130245. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.130245 |

| [46] |

ZHANG J X, ZHANG Y B, LI Y, et al. Enhancement of nitrogen removal in a novel anammox reactor packed with Fe electrode[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2012, 114: 102-108. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.018 |

| [47] |

ZHU T T, ZHANG Y B, BU G H, et al. Producing nitrite from anodic ammonia oxidation to accelerate anammox in a bioelectrochemical system with a given anode potential[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 291: 184-191. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2016.01.099 |

| [48] |

ZHOU Q M, YANG N, ZHENG D C, et al. Electrode-dependent ammonium oxidation with different low C/N ratios in single-chambered microbial electrolysis cells[J]. Bioelectrochemistry, 2021, 142: 107889. DOI:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2021.107889 |

| [49] |

HASSAN M, WEI H W, QIU H J, et al. Power generation and pollutants removal from landfill leachate in microbial fuel cell: variation and influence of anodic microbiomes[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2018, 247: 434-442. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.124 |

| [50] |

LI Y, XU Z H, CAI D Y, et al. Self-sustained high-rate anammox: from biological to bioelectrochemical processes[J]. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology, 2016, 2(6): 1022-1031. |

| [51] |

QU B, FAN B, ZHU S K, et al. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation with an anode as the electron acceptor[J]. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2014, 6(1): 100-105. DOI:10.1111/1758-2229.12113 |

| [52] |

CHAI F G, LI L, WANG W W, et al. Electro-stimulated anaerobic oxidation of methane with synergistic denitrification by adding AQS: electron transfer mode and mechanism[J]. Environmental Research, 2023, 229: 115997. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2023.115997 |

| [53] |

CHAI F G, LI L, XUE S, et al. Electrochemical system for anaerobic oxidation of methane by DAMO microbes with nitrite as an electron acceptor[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 799: 149334. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149334 |

| [54] |

VAN NIFTRIK L, VAN HELDEN M, KIRCHEN S, et al. Intracellular localization of membrane-bound ATPases in the compartmentalized anammox bacterium 'Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis'[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2010, 77(3): 701-715. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07242.x |

| [55] |

KARLSSON R, KARLSSON A, BÄCKMAN O, et al. Subcellular localization of an ATPase in anammox bacteria using proteomics and immunogold electron microscopy[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2014, 354(1): 10-18. DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12425 |

| [56] |

BRVGGEMANN H, FALINSKI F, DEPPENMEIER U. Structure of the F420H2: quinone oxidoreductase of Archaeoglobus fulgidus identification and overproduction of the F420H2-oxidizing subunit[J]. European Journal of Biochemistry, 2000, 267(18): 5810-5814. DOI:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01657.x |

| [57] |

WELTE C, DEPPENMEIER U. Re-evaluation of the function of the F420 dehydrogenase in electron transport of Methanosarcina mazei[J]. The FEBS Journal, 2011, 278(8): 1277-1287. DOI:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08048.x |

| [58] |

TIETZE M, BEUCHLE A, LAMLA I, et al. Redox potentials of methanophenazine and CoB-S-S-CoM, factors involved in electron transport in methanogenic archaea[J]. ChemBioChem, 2003, 4(4): 333-335. DOI:10.1002/cbic.200390053 |

| [59] |

MARTINEZ-ESPINOSA R M, DRIDGE E J, BONETE M J, et al. Look on the positive side! The orientation, identification and bioenergetics of 'Archaeal' membrane-bound nitrate reductases[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2007, 276(2): 129-139. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00887.x |

| [60] |

QIAO S, TIAN T, ZHOU J T. Effects of quinoid redox mediators on the activity of anammox biomass[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2014, 152: 116-123. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.11.003 |

| [61] |

KARLSSON R, KARLSSON A, BÄCKMAN O, et al. Subcellular localization of an ATPase in anam8mox bacteria using proteomics and immunogold electron microscopy[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2014, 354(1): 10-18. DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12425 |

| [62] |

SUN S S, ZHANG M P, GU X S, et al. New insight and enhancement mechanisms for feammox process by electron shuttles in wastewater treatment: a systematic review[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2023, 369: 128495. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128495 |

| [63] |

AKRAM M, BOCK J, DIETL A, et al. Specificity of small с-type cytochromes in anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. ACS Omega, 2021, 6(33): 21457-21464. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.1c02275 |

| [64] |

XIAO Y, ZHANG E, ZHANG J D, et al. Extracellular polymeric substances are transient media for microbial extracellular electron transfer[J]. Science Advances, 2017, 3(7): e1700623. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1700623 |

| [65] |

GAO Y H, WANG Y, LEE H S, et al. Significance of anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) in mitigating methane emission from major natural and anthropogenic sources: a review of AOM rates in recent publications[J]. Environmental Science: Advances, 2022, 1(4): 401-425. DOI:10.1039/D2VA00091A |

| [66] |

MCGLYNN S E, CHADWICK G L, KEMPES C P, et al. Single cell activity reveals direct electron transfer in methanotrophic consortia[J]. Nature, 2015, 526(7574): 531-535. DOI:10.1038/nature15512 |

| [67] |

MARTINEZ C M, ALVAREZ L H. Application of redox mediators in bioelectrochemical systems[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2018, 36(5): 1412-1423. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.05.005 |

| [68] |

WANG G J, TANG Z K, WEI J, et al. Effect of salinity on anammox nitrogen removal efficiency and sludge properties at low temperature[J]. Environmental Technology, 2020, 41(22): 2920-2927. DOI:10.1080/09593330.2019.1588384 |

| [69] |

LOU J Q, WANG X L, LI J P, et al. The short-and long-term effects of nitrite on denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation (DAMO) organisms[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2019, 26(5): 4777-4790. DOI:10.1007/s11356-018-3936-4 |

| [70] |

WU M L, VAN ALEN T A, VAN DONSELAAR E G, et al. Co-localization of particulate methane monooxygenase and cd1 nitrite reductase in the denitrifying methanotroph 'Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera'[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2012, 334(1): 49-56. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02615.x |

| [71] |

RASIGRAF O, KOOL D M, JETTEN M S M, et al. Autotrophic carbon dioxide fixation via the calvin-benson-bassham cycle by the denitrifying methanotroph "Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera"[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(8): 2451-2460. DOI:10.1128/AEM.04199-13 |

| [72] |

DUAN H, GAO S H, LI X, et al. Improving waste-water management using free nitrous acid (FNA)[J]. Water Research, 2020, 171: 115382. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2019.115382 |

| [73] |

YAMAMOTO S, ALCAUSKAS J B, CROZIER T E. Solubility of methane in distilled water and seawater[J]. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 1976, 21(1): 78-80. |

| [74] |

RAGHOEBARSING A A, POL A, VAN DE PASSCHOONEN K T, et al. A microbial consortium couples anaerobic methane oxidation to denitrification[J]. Nature, 2006, 440(7086): 918-921. DOI:10.1038/nature04617 |

| [75] |

CAI C, HU S H, CHEN X M, et al. Effect of methane partial pressure on the performance of a membrane biofilm reactor coupling methane-dependent denitrification and anammox[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 639: 278-285. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.164 |

| [76] |

SHI Y, HU S H, LOU J Q, et al. Nitrogen removal from wastewater by coupling anammox and methane-dependent denitrification in a membrane biofilm reactor[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(20): 11577-11583. |

| [77] |

HU S H, ZENG R J, HAROON M F, et al. A laboratory investigation of interactions between denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation (DAMO) and anammox processes in anoxic environments[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5(1): 8706. DOI:10.1038/srep08706 |

| [78] |

CAI C, HU S H, GUO J H, et al. Nitrate reduction by denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidizing microorganisms can reach a practically useful rate[J]. Water Research, 2015, 87: 211-217. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2015.09.026 |

| [79] |

WANG S H, WU Q, LEI T, et al. Enrichment of denitrifying methanotrophic bacteria from Taihu sediments by a membrane biofilm bioreactor at ambient temperature[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(6): 5627-5634. DOI:10.1007/s11356-015-5509-0 |

| [80] |

KAMPMAN C, TEMMINK H, HENDRICKX T L G, et al. Enrichment of denitrifying methanotrophic bacteria from municipal wastewater sludge in a membrane bioreactor at 20 ℃[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2014, 274: 428-435. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.04.031 |

| [81] |

MARTIN K J, NERENBERG R. The membrane biofilm reactor (MBfR) for water and wastewater treatment: principles, applications, and recent developments[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2012, 122: 83-94. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.110 |

| [82] |

TORRESI E, POLESEL F, BESTER K, et al. Diffusion and sorption of organic micropollutants in biofilms with varying thicknesses[J]. Water Research, 2017, 123: 388-400. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2017.06.027 |

| [83] |

NIE W B, DING J, XIE G J, et al. Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled with dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium fuels anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(2): 1197-1208. |

| [84] |

VANYSACKER L, BOERJAN B, DECLERCK P, et al. Biofouling ecology as a means to better understand membrane biofouling[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2014, 98(19): 8047-8072. DOI:10.1007/s00253-014-5921-2 |

| [85] |

FLEMMING H C. Biofouling and me: my stockholm syndrome with biofilms[J]. Water Research, 2020, 173: 115576. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2020.115576 |

| [86] |

FAN S Q, XIE G J, LU Y, et al. Granular sludge coupling nitrate/nitrite dependent anaerobic methane oxidation with anammox: from proof-of-concept to high rate nitrogen removal[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(1): 297-305. |

| [87] |

PENG L, FAN S Q, XIE G J, et al. Modeling nitrate/nitrite dependent anaerobic methane oxidation and Anammox process in a membrane granular sludge reactor[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 403: 125822. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125822 |

| [88] |

HE Z F, GENG S, SHEN L D, et al. The short- and long-term effects of environmental conditions on anaerobic methane oxidation coupled to nitrite reduction[J]. Water Research, 2015, 68: 554-562. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2014.09.055 |

| [89] |

KARTAL B, DE ALMEIDA N M, MAALCKE W J, et al. How to make a living from anaerobic ammonium oxidation[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2013, 37(3): 428-461. DOI:10.1111/1574-6976.12014 |

| [90] |

KUENEN J G. Anammox bacteria: from discovery to application[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2008, 6(4): 320-326. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1857 |

| [91] |

HATAMOTO M, NEMOTO S, YAMAGUCHI T. Effects of copper and PQQ on the denitrification activities of microorganisms facilitating nitrite- and nitrate-dependent DAMO reaction[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research, 2018, 12(5): 749-753. DOI:10.1007/s41742-018-0118-7 |

| [92] |

LU Y Z, FU L, LI N, et al. The content of trace element iron is a key factor for competition between anaerobic ammonium oxidation and methane-dependent denitrification processes[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 198: 370-376. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.172 |

| [93] |

VELASCO-ALVAREZ N, GONZÁLEZ I, DAMIAN-MATSUMURA P, et al. Enhanced hexadecane degradation and low biomass production by Aspergillus niger exposed to an electric current in a model system[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2011, 102(2): 1509-1515. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.07.111 |

| [94] |

WU Q, CHANG J L, YAN X X, et al. Electrical stimulation enhanced denitrification of nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane-oxidizing bacteria[J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 106: 125-128. DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2015.11.014 |

| [95] |

YIN X, QIAO S, ZHOU J T. Effects of cycle duration of an external electrostatic field on anammox biomass activity[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 19568. DOI:10.1038/srep19568 |