2. 南方海洋科学与工程广东省实验室(广州), 广东广州 511458;

3. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

4. 广西中医药大学, 广西南宁 530200

2. Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory(Guangzhou), Guangzhou, Guangdong, 511458, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China;

4. Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanning, Guangxi, 530200, China

阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer's disease, AD)是一种以语言、学习、记忆等认知能力受损为特征的慢性神经退行性疾病,同时也是痴呆最常见的病因[1]。AD目前已是65岁以上的老龄人群发病率最高的神经退行性疾病,而且随着年龄的增加,AD的发病率也在逐渐增加。根据趋势预测,到21世纪中叶,全球每85人就将出现1例AD病例[2]。目前的研究表明,AD的病理学特征主要是由细胞外的β淀粉样蛋白(β-amyloid,Aβ)沉积产生的老年斑(Senile Plaques, SP),以及在细胞内由Tau蛋白的过度磷酸化导致的神经元纤维缠结(Neurofibrillary Trangles,NFTs)[3]。AD的病因以及发病机制尚不明确,但随着研究的深入,目前已经有一部分被广泛接受的AD发病机制假说,其中包括Aβ沉积毒性、Tau蛋白异常磷酸化、基因突变、乙酰胆碱能缺失、神经炎症、氧化应激、自由基损伤、线粒体缺陷、激素缺乏、金属离子与神经元凋亡等假说[4-7]。现阶段已经上市可用于治疗AD的药物(图 1)包括他克林(tacrine,1)(已停用)[8]、多奈哌齐(donepezil,2)、卡巴拉汀(rivastigmine,3)、加兰他敏(galanthamine,4)、盐酸美金刚胺(memantine hydrochloride,5)和石杉碱甲(huperzine A, 6)(仅在中国上市),这些药都只能改善AD中轻度患者的症状,无法预防和治愈AD[9, 10]。

|

| 图 1 已上市抗AD药物结构 Fig. 1 Structures of marketed anti-AD drugs |

真菌(Fungus)广泛分布在自然界的各个角落,并且种类繁多、形态各异,是微生物三大类群之一。随着天然产物研究学者的不断努力,人们逐渐从不同来源的真菌中得到大量结构新颖复杂且具有广泛生物活性的次级代谢产物。真菌次级代谢产物的类型多为聚酮类、萜类、内酯类、生物碱类、多糖类以及肽类等,其中多数表现出抗菌、抗炎、抗肿瘤、抗病毒、抗氧化等生理活性[11, 12]。目前已经有不少学者有针对性地从分离鉴定到的真菌来源天然产物中,筛选出对治疗AD有帮助的相关靶点活性,比如抗Aβ沉积活性、乙酰胆碱酯酶(AChE)抑制活性、抗氧化应激活性,以及神经保护作用等[13]。

1 与抗A β沉积相关的真菌来源天然产物Aβ是由淀粉样前体蛋白(APP)在体内代谢后生成的具有39—43个氨基酸残基的蛋白质。APP在β分泌酶和γ分泌酶的剪切加工下会形成Aβ40/42,其中Aβ42是AD患者脑内SP的主要组成部分。研究发现,β分泌酶1(BACE1)的活性异常升高会导致AD患者脑内产生大量的不溶性多肽Aβ42,而Aβ42的不断沉积会启动一个涉及Aβ沉积、炎症、氧化应激、神经元的损伤和凋亡等的级联反应,并最终形成斑块[14]。

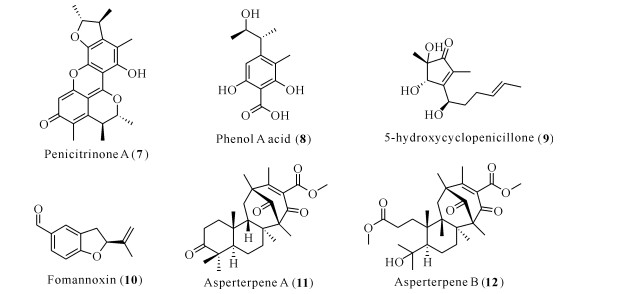

Penicitrinone A (7)和phenol A acid (8)是来源于一株深海真菌Aspergillus sp.SCSIOW3的两种橘霉素衍生物,利用硫黄素T (ThT)荧光模型进行抗Aβ42多肽聚集的活性筛选,结果显示penicitrinone A在100 μmol/L浓度下具有与阳性药表没食子儿茶素没食子酸酯(EGCG)同等水平的相对抑制率,前者为(72.25±4.38)%,EGCG为(71.20±3.26)%;单倍体phenol A acid的相对抑制率则弱一些,为(40.33±6.33)%,可见真菌来源的橘霉素衍生物penicitrinone A具有较高的抗Aβ42多肽沉积活性,显示其有抗AD的潜力[15]。Fang等[16]和Zhao等[17]从一株木霉菌Trichoderma sp.HPQJ-34的发酵提取物中分离鉴定了新环戊烯酮化合物5-hydroxycyclopenicillone (9),在体外实验中发现其可以显著降低Aβ多肽低聚物纤维化,同时具有清除2, 2-二苯基-1-甲基肼自由基的能力,并从SH-SY5Y细胞中观察到其可以显著降低H2O2诱导的细胞毒性,这些证据表明5-hydroxycyclopenicillone可以从抗Aβ沉积和抗氧化应激两方面保护神经元细胞。

苯并呋喃类化合物被证实可以作为γ-分泌酶、BACE1、Tau蛋白错误折叠和Aβ聚集的抑制剂,对AD的治疗具有良好应用前景[18]。但是研究者们多采用合成的苯并呋喃类化合物来测试活性,真菌来源的天然苯并呋喃鲜有抗AD相关活性的报道。2018年,González-Ramírez等[19]对来自Aleurodiscus vitellinus的苯并呋喃衍生物fomannoxin (10)进行抗Aβ聚集活性测试,结果显示fomannoxin可以在1 μmol/L的浓度下对抗5 μmol/L Aβ造成的细胞毒性,神经元PC12细胞存活率达100%;更深入的试验发现,fomannoxin通过干扰Aβ与细胞质膜的结合,从而达到消除Aβ介导的细胞毒性的目的。

Asperterpenes A (11)和B (12)是来源于曲霉Aspergillus terreus的新骨架二萜类化合物,可在体外抑制BACE1,其半数抑制浓度(50% Inhibitory Concentration, IC50)分别为78和59 nmol/L,活性均优于阳性对照LY2811376 (IC50=260 nmol/L);在AD模型小鼠体内,asperterpene A表现出与LY2811376相似的抑制BACE1活性,降低了Aβ的产生[20]。

以上化合物的化学结构见图 2。

|

| 图 2 具有抗Aβ活性的化合物结构(7—12) Fig. 2 Structures of compounds with anti-Aβ activity (7—12) |

2 与乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂相关的真菌来源天然产物

乙酰胆碱能缺失假说是AD发病假说中最经典的假说。乙酰胆碱是神经系统中非常重要的神经递质之一,能与学习和记忆相关的受体结合发挥作用。胆碱酯酶主要作用是分解神经突触间隙的胆碱能,终止胆碱与突触后膜的相互作用。根据作用底物的特异性,胆碱酯酶可分为乙酰胆碱酯酶(AChE)和丁酰胆碱酯酶(BuChE)。乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂(AChEI)可以抑制AChE,减少乙酰胆碱的分解,提高乙酰胆碱在突触间隙的含量,增强胆碱能传递,保护神经元[21]。目前已经上市的抗AD药物,除了盐酸美金刚胺,其余皆为AChEI。因此,寻找可靠有效的AChEI也是抗AD药物开发的一大方向。

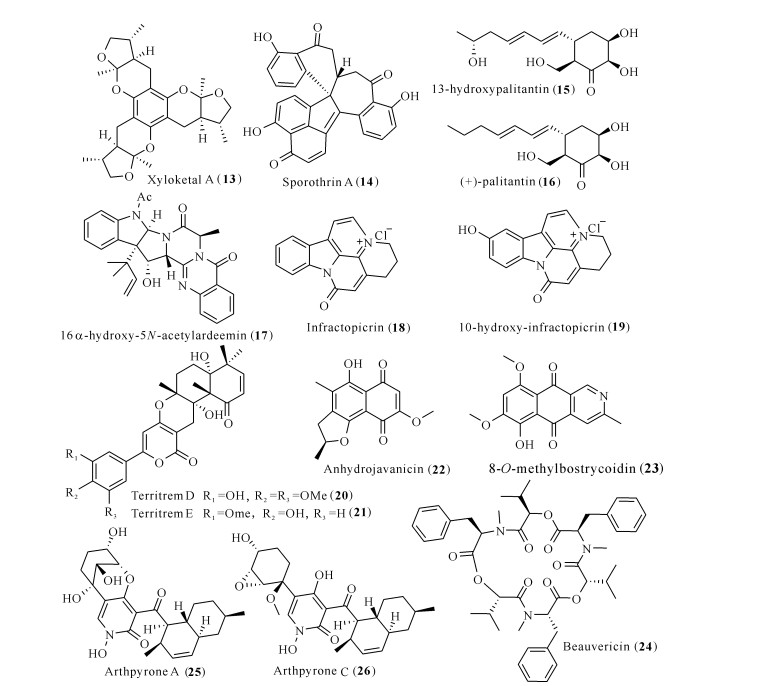

2006年,Houghton等[22]综述了来源于植物和真菌的具有抑制胆碱酯酶活性的天然产物,以下讨论从2007至今所报道的部分来源于真菌的胆碱酯酶抑制剂(图 3)。

|

| 图 3 具有抗AChE活性的化合物结构(13—26) Fig. 3 Structures of compounds with anti-AChE activity (13—26) |

Xyloketal A (13)是来源于一株南海红树林真菌Xylaria sp.的聚酮类化合物,其在1.5 μmol/L的浓度下对AChE表现出显著的抑制作用(P < 0.01)[23]。从另外一株红树林内生真菌Sporothrix sp.#4335中分离得到的,具有罕见骨架的聚酮类化合物sporothrin A (14),在体外也表现出较强的抑制AChE活性,IC50为1.05 μmol/L[24]。聚酮类化合物13-hydroxypalitantin (15)和(+)-palitantin (16)来源于红树林内生真菌Penicillium sp.sk14JW2P,体外AChE抑制活性测试显示其具有显著的抗AChE活性,IC50分别为(12±0.3)和(79±2) nmol/L[25]。

来源于植物内生真菌Aspergillus terreus的吲哚类生物碱16α-hydroxy-5N-acetylardeemin (17),具有与阳性药他克林相当的抑制AChE活性,前者IC50为(58.3±3.3) μmol/L,后者IC50为(37.9±3.8) μmol/L[26]。另外两个来源于Cortinarius infractus Berk的生物碱infractopicrin (18)和10-hydroxy-infractopicrin (19)同样具有抑制AChE活性(IC50分别是9.72和12.7 μmol/L),其活性与加兰他敏相当(IC50为8.70 μmol/L)[27]。从一株海洋来源的曲霉属真菌Aspergillus terreus SCSGAF0162发酵提取物中分离鉴定到的两个内酯类territrem衍生物(20和21),展现出比阳性药石杉碱甲更强的AChE抑制活性,前两者IC50分别为(4.2±0.6)和(4.5±0.6) nmol/L,后者IC50为(39.3±7.6) nmol/L[28]。来源于另一株海洋曲霉属真菌Aspergillus terreus (No.GX7-3B)的anhydrojavanicin (22)、8-O-methylbostrycoidin (23)和环肽beauvericin (24),这3个化合物皆对α-AChE有显著的抑制活性,IC50分别为2.01,6.71和3.09 μmol/L[29]。Wang等[30]从一株来源于西沙海绵的共附生节菱孢菌Arthrinium arundinis ZSDS1-F3中,分离鉴定了两个具有抗AChE活性的萘环吡啶酮生物碱(25和26),IC50分别为47和0.81 μmol/L。

3 与抗神经炎症相关的真菌来源天然产物神经炎症是AD患者脑内主要病理特征之一,是一种复杂的脑损伤反应,涉及胶质细胞的激活,炎症介质如细胞因子和趋化因子的释放, 以及活性氧、活性氮的生成。正常情况下,脑内的小胶质细胞和星形胶质细胞可以检测脑内异常情况,清除有害因子,防止大脑损伤。在AD发病进程中,Aβ的异常沉积导致小胶质细胞和星形胶质细胞被持续异常激活,逐渐分泌白细胞介素(IL,包括IL-1β和IL-6)和肿瘤坏死因子(TNF,包括TNF-α和TNF-γ)等细胞炎症因子,诱导神经炎症的产生,最终造成神经元细胞损伤或者凋亡[31, 32]。此外胶质细胞分泌产生的环氧合酶-2(COX-2)和一氧化氮合酶(iNOS)会促进神经元细胞的氧化应激水平,进一步损伤神经元细胞。有研究表明,细胞因子IL-17在AD神经炎症早期阶段活化胶质细胞,对神经系统可能起保护作用,但是在AD神经炎症晚期阶段,胶质细胞持续活化,在IL-17的参与下会诱导神经元和神经胶质细胞凋亡,加重AD的病理损伤。因此,调控IL-17信号通路的关键因子可能成为有前景的AD治疗新靶点[33]。

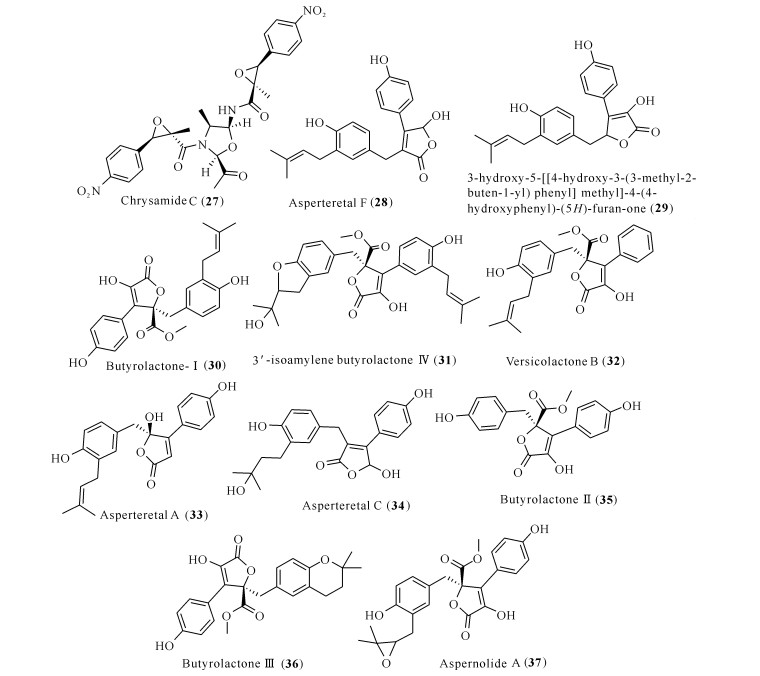

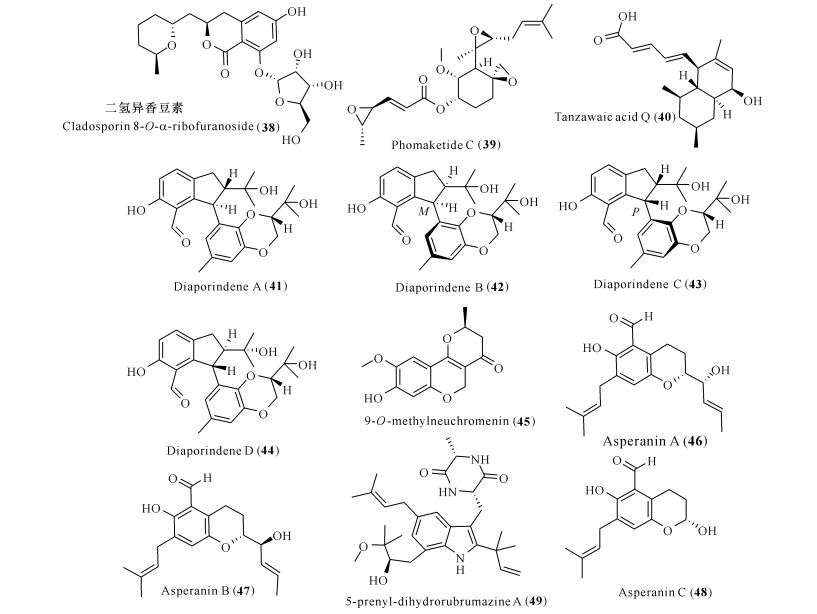

Chen等[34]从一株深海来源的青霉属真菌Penicillium chrysogenum SCSIO41001的发酵提取物中,分离得到具有抗促炎因子IL-17表达活性的chrysamide C (27),活性测试表明,在10 μmol/L的浓度下,抑制率可达(62.61±0.55)%。Yang等[35]从一株分离自南海沿岸沉积物的真菌Aspergillus terreus Y10的培养液乙酸乙酯萃取物中,分离得到丁烯内酯类化合物28和29,将BV-2小胶质细胞与这两个化合物(10 μg/mL)预孵育1 h,然后用脂多糖(LPS)诱导6 h,检测TNF-α的产生作为细胞活化的标志,同时细胞毒测试表明化合物对BV-2小胶质细胞无毒性作用,在这种情况下,化合物28和29对TNF-α产生的抑制率分别达55.1%和35.5%;在0.6—40.0 μg/mL浓度下,化合物28和29的IC50分别为(7.6±1.1)和(9.90±1.06) μg/mL。来源于另外一株珊瑚内生真菌Aspergillus terreus的丁内酯Ⅰ (butyrolactone-Ⅰ)(30),可降低LPS诱导BV-2小胶质细胞造成的炎症反应,同时还可以降低NO和IL-1β的产生;分子印迹和分子对接实验表明,丁内酯Ⅰ能通过抑制炎症信号通路NF-κB相关因子的磷酸化从而抑制神经炎症,同时丁内酯Ⅰ也是COX-2的潜在抑制剂[36]。除丁内酯Ⅰ外,一系列丁内酯类衍生物(31—37)也表现出抑制NO生成的活性。研究人员利用LPS在小鼠RAW264.7巨噬细胞内诱导NO的产生作为指标,将巨噬细胞与化合物孵育后检测各自的NO抑制率,结果发现在20 μmol/L浓度下,化合物31和32的NO抑制率分别达25.1%和25.3%[37];而化合物33-37抑制NO的IC50为16.80-45.37 μmol/L [38]。

以上化合物的化学结构见图 4。

|

| 图 4 具有抗神经炎症活性的化合物结构(27—37) Fig. 4 Structures of compounds with anti-neuroinflammatory activity (27—37) |

前列腺素E2(PGE2)的水平升高也与脑内的炎症反应有关,其可以通过与4种不同G蛋白偶联受体共同介导小胶质细胞的旁分泌神经毒性,使小胶质细胞分泌活动异常[39]。Kim等[40]从曲霉属Aspergillus sp.SF-5974和Aspergillus sp.SF-5976的液体共培养发酵物中,分离鉴定出一个新颖的二氢异香豆素(38),活性测试发现其能通过抑制iNOS和COX-2的表达,从而抑制LPS诱导的NO和PGE2的释放。对靶点iNOS和COX-2具有抑制活性的真菌代谢产物还有聚酮类化合物phomaketide C (39)[41]、tanzawaic acid Q(40)[42]、diaporindenes A—D(41—44)[43]、9-O-methylneuchromenin(45)[44],苯甲醛衍生物asperanins A—C (46—48)以及二酮哌嗪生物碱5-prenyl-dihydrorubrumazine A(49)[45]。以上化合物抑制NO或者PGE2释放的IC50为4.2—28.2 μmol/L,具有发展成抗神经炎症的先导药物的前景(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 具有抗神经炎症活性的化合物结构(38—49) Fig. 5 Structures of compounds with anti-neuroinflammatory activity (38—49) |

4 与抗氧化活性相关的真菌来源天然产物

在AD的发病进程中,Aβ通过刺激神经元细胞产生大量的氧自由基,造成脑部细胞成分中的脂质和蛋白被氧化,活性氧的含量增加;或者由于神经炎症导致活性氧和活性氮含量增加令脑组织产生损伤。具有抗氧化活性的化合物可以清除氧自由基或者防止活性自由基的产生。

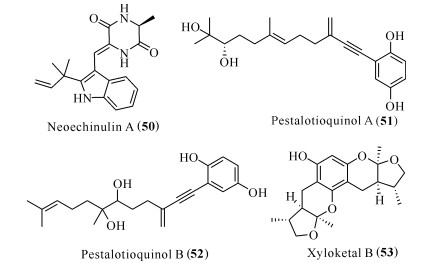

从一株赤散囊菌Eurotium rubrum Hiji025中分离出的neoechinulin A(50)被证实具有神经保护作用,其能够使神经元PC12细胞免受过氧硝酸盐生成剂3-morpholino-sydnonimine (SIN-1)诱导的细胞毒性[46]。研究发现,neoechinulin A主要是对抗由NO或者NO生成剂(如SIN-1)导致的亚硝化应激,而不是类似H2O2引起的氧化应激,并且neoechinulin A需要高浓度才可以起到神经保护活性[47]。利用同样的方法,两个带乙烯基炔烃的对苯二酚衍生物pestalotioquinols A (51)和B (52),也被证实可以使神经生长因子诱导分化的PC12细胞免受SIN-1诱导的细胞毒作用[48]。Kanno等[48]通过构效分析发现,对苯二酚基团对pestalotioquinols A和B的神经保护活性具有重要作用,如果羟基被甲氧基取代,活性将大大降低,并且pestalotioquinols A和B能在1—3 μmol/L浓度下发挥作用,活性远远大于neoechinulin A,表明pestalotioquinols A和B在开发抗AD药物方面具有更大的前景。此外,来源于红树林内生真菌Xylaria sp.的xyloketal B (53),被证实在体外可以防止氧化低密度脂质蛋白导致的细胞损伤[49],通过抑制产生ROS和活性氮的酶及增强抗氧化酶来降低自由基水平[50],防止自由基过高损伤细胞;增加抗凋亡蛋白的表达来抑制线粒体损伤和细胞凋亡的启动;同时xyloketal B对缺糖诱导损伤的PC12细胞也表现出神经保护作用活性[51]。Xyloketal B是研究较多的、具有多靶点抑制活性的真菌来源天然产物,有广阔的成药前景。

以上化合物的化学结构见图 6。

|

| 图 6 具有抗氧化活性的化合物结构(50—53) Fig. 6 Structures of compounds with antioxidant activity(50—53) |

5 与神经营养活性相关的真菌来源天然产物

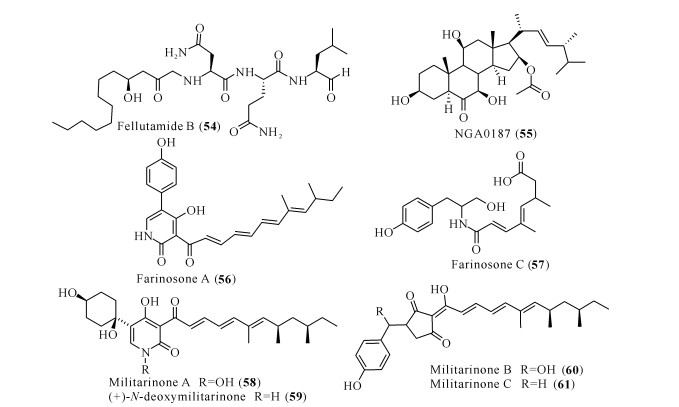

健康神经元的活性是由神经营养素促进和维持的,神经营养素往往参与多个神经元生理过程的调节,包括神经元的存活、轴突的生长以及神经干细胞的分化等[52]。神经生长因子(Nerve Growth Factor,NGF)是第一个发现的,也是最具特征的神经营养素。其他神经营养素家族成员包括脑源性神经营养因子(BDNF)、神经营养素-3 (NT-3)、神经营养素-4/5 (NT-4/5)、神经营养靶标的调节剂如NGF受体酪氨酸蛋白激酶A (Tyrosine Kinase A,TrkA)等,对于治疗包括AD在内的神经退行性疾病都具有巨大的潜力[53]。目前已有不少天然产物被报道具有类神经营养因子的作用,可以促进神经元细胞生长和分化[54]。其中来源于Penicillium fellutanum的天然产物fellutamide B (54),能够诱导成纤维细胞和胶质细胞释放NGF,其作用机理是通过抑制蛋白酶体,促进NGF的基因表达[55]。从Acremonium sp.TF-0356发酵液中分离得到的聚酮类化合物NGA0187(55),在30 μg/mL的浓度下具有诱导PC12细胞突触生长的作用,活性与NGF相当[56]。同样地,来源于菌株Paecilomyces farinosus RCEF 0101的两个生物碱farinosones A (56)和C (57),在50 μmol/L浓度下也表现出增强PC12细胞突触生长的营养活性,而且在此浓度下没有观察到对PC12细胞具有细胞毒活性,但是神经营养活性低于NGF[57]。Paecilomyces militaris来源的生物碱类化合物militarinone在2002年就被证实具有神经营养活性,其中militarinone A (58)的活性最高,在10 μmol/L浓度下就可以促进PC12细胞的突触生长,且没有表现出细胞毒活性[58]。Militarinone A的脱羟基衍生物(+)-N-deoxymilitarinone (59)则需要在100 μmol/L浓度下才能表现神经营养活性,但该浓度下其对人神经元细胞IMR-32表现出细胞毒性[59]。Militarinones B (60)和C (61)的神经营养活性更弱,在100 μmol/L的浓度下只能边缘性增强PC12细胞的突触生长[60]。

一系列异戊二烯色氨酸来源的生物碱(62-68)从一株米曲霉大米培养基的发酵产物中分离得到,并且同时表现出神经保护活性和神经营养活性;在100 μmol/L浓度下,化合物63,64和66—68可以对抗PC12细胞中H2O2诱导的氧化应激,将细胞存活率从47.29%提高至70.16%-90.85%;在25—100 μmol/L浓度下,化合物62—68均能促进未分化的PC12细胞轴突的生长,表现出神经营养活性[61]。

|

| 图 7 具有神经营养活性的化合物结构(54—61) Fig. 7 Structures of compounds with neurotrophic activity (54—61) |

|

| 图 8 具有神经营养活性的化合物结构(62—68) Fig. 8 Structures of compounds with neurotrophic activity (62—68) |

6 展望

AD的发病机制尚不明确,涉及因素众多,给抗AD药物的筛选带来非常大的挑战和困难。所以,深入了解AD病理特征,探索更多有效的治疗靶点,建立能更好模拟AD病理特征的生物学模型,优化药物筛选途径,寻找多靶标抑制剂等,将是科研工作者未来努力的重要方向。真菌种类繁多,且能够产生大量结构独特、活性新颖的次级代谢产物,是寻找治疗各种疾病先导药物的巨大宝库。已在我国上市的抗AD药物石杉碱甲,是从我国中草药蛇足石杉(Huperzia serrata)中提取分离到的一种强活性倍半萜类生物碱,具有很强的抗AChE活性、抗氧化应激,抑制Aβ沉积和上调抗凋亡蛋白等多重神经保护作用[62]。近几年来,已有不少学者从蛇足石杉或其他植物中分离得到多种具有产石杉碱甲能力的内生真菌,如Fusarium sp.Rsp5.2和Fusarium oxysporum NSG-1等[63-66]。未来可以设计培育石杉碱甲高产菌株,通过发酵条件优化达到工业生产水平。研究此类内生真菌还可以获得石杉碱甲衍生物,为筛选新的抗AD药物提供很大可能性。这同时预示着真菌来源的天然产物将来会是寻找抗AD药物的一个新领域,相信随着分离技术和活性筛选技术的不断发展和进步,会有更多的具有抗AD活性的真菌天然产物被发现,为人类社会解决AD这一世界难题提供新动力。

| [1] |

GAUGLER J, JAMES B, JOHNSON T, et al. Alzhei-mer's disease facts and figures[J]. Alzhmer's & Dementia, 2016, 12(4): 459-509. |

| [2] |

ANAND A, PATIENCE A A, SHARMA N, et al. The present and future of pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's disease:A comprehensive review[J]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2017, 815: 364-375. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.09.043 |

| [3] |

LANE C A, HARDY J, SCHOTT J M. Alzheimer's disease[J]. European Journal of Neurology, 2018, 25(1): 59-70. |

| [4] |

COHEN T J, GUO J L, HURTADO D E, et al. The acetylation of tau inhibits its function and promotes pathological tau aggregation[J]. Nature Communications, 2011, 2(1): 252. |

| [5] |

DELACOURTE A. Amyloid precursor protein neuro-trophic properties as a target to cure Alzheimer's disease[J]. European Neurological Review, 2006, 6(1): 29-30. |

| [6] |

CALSOLARO V, EDISON P. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease:Current evidence and future directions[J]. Alzheimer's Dementia, 2016, 12(6): 719-732. DOI:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.010 |

| [7] |

SCHELTENS P, BLENNOW K, BRETELER M M B, et al. Alzheimer's disease[J]. The Lancet, 2016, 388(10043): 505-517. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1 |

| [8] |

张营丽, 唐伟, 王威. 阿尔茨海默病诊断与治疗策略[J]. 中国老年学杂志, 2015, 35(3): 862-864. |

| [9] |

ADLIMOGHADDAM A, NEUENDORFF M, ROY B, et al. A review of clinical treatment considerations of donepezil in severe Alzheimer's disease[J]. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 2018, 24(10): 876-888. |

| [10] |

MEI Z R, ZHENG P Y, TAN X P, et al. Huperzine a alleviates neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and improves cognitive function after repetitive traumatic brain injury[J]. Metabolic Brain Disease, 2017, 32(6): 1861-1869. DOI:10.1007/s11011-017-0075-4 |

| [11] |

RATEB M E, EBEL R. Secondary metabolites of fungi from marine habitats[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2011, 28(2): 290-344. |

| [12] |

王景仪, 李梦秋, 李艳茹, 等. 药用植物内生真菌的多样性及生物功能研究进展[J]. 生物资源, 2020, 42(2): 164-172. |

| [13] |

张翠仙, 彭光天, 何细新, 等. 中国海洋共附生真菌次生代谢产物最新研究进展[J]. 天然产物研究与开发, 2013, 25(9): 1284-1291, 1273. |

| [14] |

O'BRIEN R J, WONG P C. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 2011, 34: 185-204. DOI:10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613 |

| [15] |

刘海, 孔明珠, 郑易之, 等. 深海来源真菌Aspergillus sp.SCSIOW3抗A-beta多肽聚集活性成分的研究[J]. 中国海洋药物, 2014, 33(6): 71-74. |

| [16] |

FANG F, ZHAO J Y, DING L J, et al. 5-hydroxycyclopenicillone, a new beta-amyloid fibrillization inhibitor from a sponge-derived fungus Trichoderma sp.HPQJ-34[J]. Marine Drugs, 2017, 15(8): 260. DOI:10.3390/md15080260 |

| [17] |

ZHAO J Y, LIU F F, HUANG C H, et al. 5-hydroxycyclopenicillone inhibits beta-amyloid oligomerization and produces anti-beta-amyloid neuroprotective effects in vitro[J]. Molecules, 2017, 22(10): 1651. DOI:10.3390/molecules22101651 |

| [18] |

RIZZO S, RIVIERE C, PIAZZI L, et al. Benzofuranba-sed hybrid compounds for the inhibition of cholinesterase activity, beta amyloid aggregation, and abeta neurotoxicity[J]. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2008, 51(10): 2883-2886. DOI:10.1021/jm8002747 |

| [19] |

GONZÁLEZ-RAMÍREZ M, GAVILAN J, SILVA-GRECCHI T, et al. A natural benzofuran from the patagonic Aleurodiscus vitellinus fungus has potent neuroprotective properties on a cellular model of amyloid-beta peptide toxicity[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2018, 61(4): 1463-1475. DOI:10.3233/JAD-170958 |

| [20] |

QI C X, BAO J, WANG J P, et al. Asperterpenes A and B, two unprecedented meroterpenoids from Aspergillus terreus with BACE1 inhibitory activities[J]. Chemical Science, 2016, 7(10): 6563-6572. DOI:10.1039/C6SC02464E |

| [21] |

LEONETTI F, CATTO M, NICOLOTTI O, et al. Homo- and hetero-bivalent edrophonium-like ammonium salts as highly potent, dual binding site AChE inhibitors[J]. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 2008, 16(15): 7450-7456. |

| [22] |

HOUGHTON P J, REN Y, HOWES M J. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from plants and fungi[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2006, 23(2): 181-199. |

| [23] |

LIN Y, WU X, FENG S, et al. Five unique compounds:Xyloketals from mangrove fungus Xylaria sp.from the South China Sea Coast[J]. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2001, 66(19): 6252-6256. |

| [24] |

WEN L, CAI X L, XU F, et al. Three metabolites from the mangrove endophytic fungus Sporothrix sp.(#4335) from the South China Sea[J]. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2009, 74(3): 1093-1098. |

| [25] |

HUANG X S, YANG B, SUN X F, et al. A new olyketide from the mangrove endophytic fungus Penicillium sp.sk14JW2P[J]. Helvetica Chimica Acta, 2014, 97(5): 664-668. |

| [26] |

GE H M, PENG H, GUO Z K, et al. Bioactive alkaloids from the plant endophytic fungus Aspergillus terreus[J]. Planta Medica, 2010, 76(8): 822-824. |

| [27] |

GEISSLER T, BRANDT W, PORZEL A, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from the toadstool Cortinarius infractus[J]. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 2010, 18(6): 2173-2177. |

| [28] |

NONG X H, WANG Y F, ZHANG X Y, et al. Territrem and butyrolactone derivatives from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus[J]. Marine Drugs, 2014, 12(12): 6113-6124. |

| [29] |

DENG C M, LIU S X, HUANG C H, et al. Secondary metabolites of a mangrove endophytic fungus Aspergillus terreus (No.GX7-3B) from the South China Sea[J]. Marine Drugs, 2013, 11(7): 2616-2624. |

| [30] |

WANG J F, WEI X Y, QIN X C, et al. Arthpyrones A-C, pyridone alkaloids from a sponge-derived fungus Arthrinium arundinis ZSDS1-F3[J]. Organic Letters, 2015, 17(3): 656-659. |

| [31] |

JAWORSKI T, LECHAT B, DEMEDTS D, et al. Dendritic degeneration, neurovascular defects, and inflammation precede neuronal loss in a mouse model for tau-mediated neurodegeneration[J]. The American Journal of Pathology, 2011, 179(4): 2001-2015. |

| [32] |

MATOUSEK S B, GHOSH S, SHAFTEL S S, et al. Chronic IL-1β-mediated neuroinflammation mitigates amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease without inducing overt neurodegeneration[J]. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, 2012, 7(1): 156-164. |

| [33] |

方杰.IL-17在阿尔茨海默病中的作用及机制研究[D].福州: 福建医科大学, 2015.

|

| [34] |

CHEN S T, WANG J F, LIN X P, et al. Chrysamides A-C, three dimeric nitrophenyl trans-epoxyamides produced by the deep-sea-derived fungus Penicillium chrysogenum SCSIO41001[J]. Organic Letters, 2016, 18(15): 3650-3653. |

| [35] |

YANG L H, OU-YANG H, YAN X, et al. Open-ring butenolides from a marine-derived anti-neuroinflammatory fungus Aspergillus terreus Y10[J]. Marine Drugs, 2018, 16(11): 428. |

| [36] |

ZHANG Y Y, ZHANG Y, YAO Y B, et al. Butyrolactone-Ⅰ from coral-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus attenuates neuro-inflammatory response via suppression of NF-κB pathway in BV-2 cells[J]. Marine Drugs, 2018, 16(6): 202. |

| [37] |

LIU M T, ZHOU Q, WANG J P, et al. Anti-inflammatory butenolide derivatives from the coral-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus and structure revisions of aspernolides D and G, butyrolactone Ⅵ and 4', 8''-diacetoxy butyrolactone Ⅵ[J]. RSC Advances, 2018, 8(23): 13040-13047. |

| [38] |

GUO F, LI Z L, XU X W, et al. Butenolide derivatives from the plant endophytic fungus Aspergillus terreus[J]. Fitoterapia, 2016, 113: 44-50. |

| [39] |

WANG T, QIN L, LIU B, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in LPS-induced production of prostaglandin E2 in microglia[J]. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2004, 88(4): 939-947. |

| [40] |

KIM D C, QUANG T H, NGAN N T, et al. Dihydroi-socoumarin derivatives from marine-derived fungal isolates and their anti-inflammatory effects in lipopolysaccharide-induced BV2 microglia[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2015, 78(12): 2948-2955. |

| [41] |

LEE M S, WANG S W, WANG G J, et al. Angiogenesis inhibitors and anti-inflammatory agents from Phoma sp.NTOU4195[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2016, 79(12): 2983-2990. |

| [42] |

SHIN H J, PIL G B, HEO S J, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of tanzawaic acid derivatives from a marine-derived fungus Penicillium steckii 108YD142[J]. Marine Drugs, 2016, 14(1): 14. |

| [43] |

CUI H, LIU Y N, LI J, et al. Diaporindenes A-D:Four unusual 2, 3-dihydro-1 H-indene analogues with anti-inflammatory activities from the mangrove endophytic fungus Diaporthe sp.SYSU-HQ3[J]. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2018, 83(19): 11804-11813. |

| [44] |

HA T M, KIM D C, SOHN J H, et al. Anti-inflammatory and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitory metabolites from the antarctic marine-derived fungal strain Penicillium glabrum SF-7123[J]. Marine Drugs, 2020, 18(5): 247. |

| [45] |

KWON J, LEE H, KO W, et al. Chemical constituents isolated from Antarctic marine-derived Aspergillus sp.SF-5976 and their anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 and BV2 cells[J]. Tetrahedron, 2017, 73(27/28): 3905-3912. |

| [46] |

MARUYAMA K, OHUCHI T, YOSHIDA K, et al. Protective properties of neoechinulin A against SIN-1-induced neuronal cell death[J]. Journal of Biochemistry, 2004, 136(1): 81-87. |

| [47] |

AKASHI S, SHIRAI K, OKADA T, et al. Neoechinulin a imparts resistance to acute nitrosative stress in PC12 cells:A potential link of an elevated cellular reserve capacity for pyridine nucleotide redox turnover with cytoprotection[J]. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2012, 35(7): 1105-1117. |

| [48] |

KANNO K, TSURUKAWA Y, KAMISUKI S, et al. Novel neuroprotective hydroquinones with a vinyl alkyne from the fungus, Pestalotiopsis microspora[J]. The Journal of Antibiotics (Tokyo), 2019, 72(11): 793-799. |

| [49] |

CHEN W L, QIAN Y, MENG W F, et al. A novel marine compound xyloketal B protects against oxidized LDL-induced cell injury in vitro[J]. Biochemical Pharmacology, 2009, 78(8): 941-950. |

| [50] |

GONG H F, LUO Z W, CHEN W L, et al. Marine compound xyloketal B as a potential drug development target for neuroprotection[J]. Marine Drugs, 2018, 16(12): 516. |

| [51] |

ZHAO J, LI L, LING C, et al. Marine compound xyloketal B protects PC12 cells against OGD-induced cell damage[J]. Brain Research, 2009, 1302: 240-247. |

| [52] |

PRICE R D, MILNE S A, SHARKEY J, et al. Advances in small molecules promoting neurotrophic function[J]. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 2007, 115(2): 292-306. |

| [53] |

CONNOR B, DRAGUNOW M. The role of neuronal growth factors in neurodegenerative disorders of the human brain[J]. Brain Research Review, 1998, 27(1): 1-39. |

| [54] |

TOHDA C, KUBOYAMA T, KOMATSU K. Search for natural products related to regeneration of the neuronal network[J]. Neurosignals, 2005, 14(1/2): 34-45. |

| [55] |

HINES J, GROLL M, FAHNESTOCK M, et al. Proteasome inhibition by fellutamide B induces nerve growth factor synthesis[J]. Cell Chemical Biology, 2008, 15(5): 501-512. |

| [56] |

NOZAWA Y, SAKAI N, MATSUMOTO K, et al. A novel neuritogenic compound, NGA0187[J]. The Journal of Antibiotics (Tokyo), 2002, 55(7): 629-634. |

| [57] |

CHENG Y X, SCHNEIDER B, RIESE U, et al. Farinosones A-C, neurotrophic alkaloidal metabolites from the entomogenous deuteromycete Paecilomyces farinosus[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2004, 67(11): 1854-1858. |

| [58] |

SCHMIDT K, GUNTHER W, STOYANOVA S, et al. Militarinone A, a neurotrophic pyridone alkaloid from Paecilomyces militaris[J]. Organic Letters, 2002, 4(2): 197-199. |

| [59] |

CHENG Y X, SCHNEIDER B, RIESE U, et al. (+)-N-deoxymilitarinone A, a neuritogenic pyridone alkaloid from the insect pathogenic fungus Paecilomyces farinosus[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2006, 69(3): 436-438. |

| [60] |

SCHMIDT K, RIESE U, LI Z, et al. Novel tetramic acids and pyridone alkaloids, militarinones B, C, and D, from the insect pathogenic fungus Paecilomyces militaris[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2003, 66(3): 378-383. |

| [61] |

LIU L, BAO L, WANG L, et al. Asperorydines A-M:Prenylated tryptophan-derived alkaloids with neurotrophic effects from Aspergillus oryzae[J]. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2018, 83(2): 812-822. |

| [62] |

GAO X, ZHENG C Y, YANG L, et al. Huperzine A protects isolated rat brain mitochondria against β-amyloid peptide[J]. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 2009, 46(11): 1454-1462. |

| [63] |

LE T T M, HOANG A T H, NGUYEN N P, et al. A novel huperzine A-producing endophytic fungus Fusarium sp.Rsp5.2 isolated from Huperzia serrate[J]. Biotechnology Letters, 2020, 42(6): 987-995. |

| [64] |

WANG Y, ZENG Q G, ZHANG Z B, et al. Isolation and characterization of endophytic huperzine A-producing fungi from Huperzia serrata[J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 2011, 38(9): 1267-1278. |

| [65] |

ISHIUCHI K, HIROSE D, SUZUKI T, et al. Identifi-cation of Lycopodium alkaloids produced by an ultraviolet-irradiated strain of Paraboeremia, an endophytic fungus from Lycopodium serratum var.longipetiolatum[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2018, 81(5): 1143-1147. |

| [66] |

韩文霞, 李伟泽, 李小峰, 等. 蛇足石杉内生真菌产石杉碱甲含量检测及真菌的鉴定[J]. 国际药学研究杂志, 2016, 43(6): 1112-1116. |