2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

3. 北京顺鑫农业股份有限公司牛栏山酒厂, 北京 101301;

4. 山西汾酒集团股份有限公司, 山西汾阳 032205;

5. 广西天龙泉酒业有限公司, 广西河池 546400

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China;

3. Niulanshan Distillery, Shunxin Agriculture Co. Ltd., Beijing, 101301, China;

4. Shanxi Fenjiu Co. Ltd., Fenyang, Shanxi, 032205, China;

5. Tianlongquan Distillery Co. Ltd., Hechi, Guangxi, 546400, China

扣囊复膜酵母(Saccharomycopsis fibuligera),又称拟内孢霉,是子囊菌门(Ascomycota)酵母亚门(Saccharomycotina)下酵母纲(Saccharomycetes)酵母目(Saccharomycetales)酵母科(Saccharomycetaceae)复膜酵母属(Saccharomycopsis)的一个种[1-2]。自Wickerham等[3]首次报道利用S.fibuligera水解淀粉以来,已有大量关于该物种产酶等性状的研究。扣囊复膜酵母作为优势菌株广泛存在于淀粉质含量高的酒曲(如韩国酒曲Nuruk[4]、泰国酒曲Loog-pang[5]、红曲和药曲[6]、我国清香型白酒酒曲[7-9]等)和发酵前期的酒醅中,且随着发酵进行数量迅速减少[4, 10]。扣囊复膜酵母还对白酒香型、风味形成具有贡献价值。本文介绍了扣囊复膜酵母的基本特征、产酶特性及其对白酒风味物质的影响,为利用组合菌株生产酒精饮料或筛选优良菌株用于白酒纯种发酵提供参考依据。

1 扣囊复膜酵母的基本特征了解扣囊复膜酵母的基本特征是运用该菌种进行白酒纯种发酵的基础,也是改良白酒生产工艺条件的依据。对扣囊复膜酵母基因组信息的解读,有助于研究其次级代谢产物及调控规律,从而提高对酒体、风味物质的可操控性和稳定性。

扣囊复膜酵母具有典型的二型性,既存在大量分支状的有隔假菌丝,又产生酵母状的芽殖细胞[11]。当转录调控因子、Mig1(Multicopy Inhibitor of GAL Gene Expression)失活[12],在碳源限制条件下培养(培养基中葡萄糖≤0.1%)或在培养基中加入线粒体呼吸链抑制剂抗霉素A(Antimycin A)[11]时,菌株趋向于酵母态生长。该酵母有性繁殖产生球形或卵圆形的子囊,呈游离状或附着于菌丝末端或者侧面。每个子囊可以形成2-4个帽子状的子囊孢子,并在成熟时释放[2]。

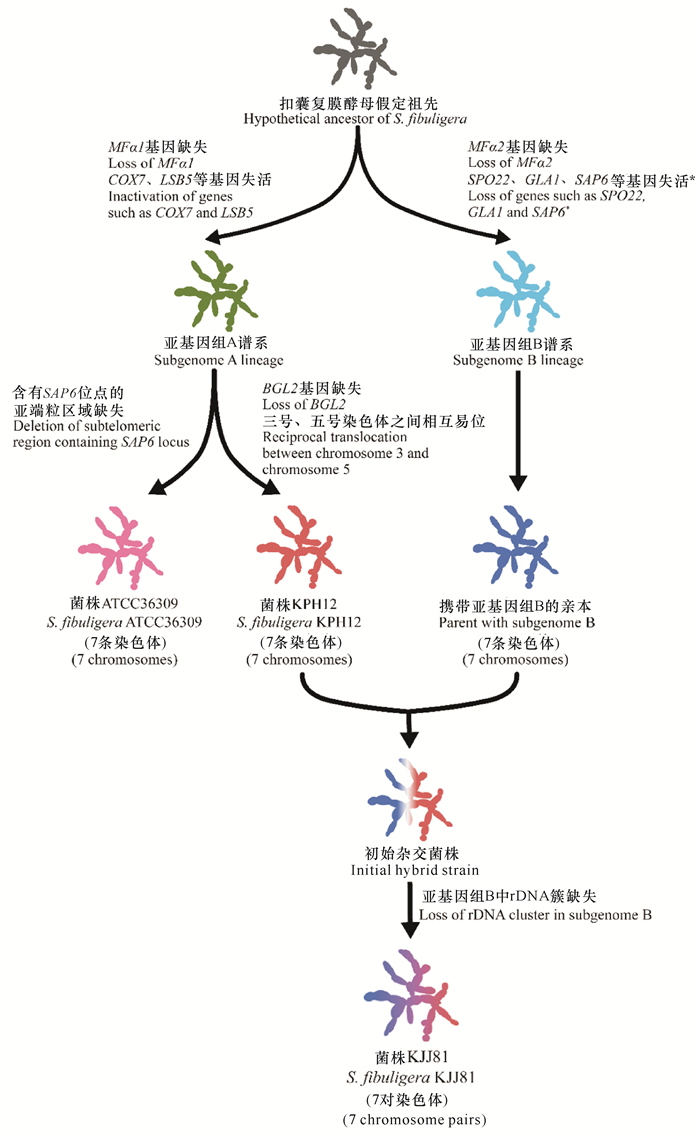

目前已公布的基因组分析结果[11]如表 1所示。杂合菌株KJJ81包含两个亚基因组(A型和B型)。推测由一共同祖先分化为两个谱系(A型和B型),从A型谱系中分化出菌株KPH12和ATCC36309。菌株KPH12与B型谱系菌株杂交,得到菌株KJJ81的祖先,丢失部分序列后形成菌株KJJ81[11](图 1)。虽然在酒曲中检测到了B型谱系的菌株,但目前尚未分离到该谱系的纯菌株[13]。

| Strain | Genome size (Mb) | Protein-coding gene number | Scaffold number | Genome sequence identity (%) with | Mitochondrial genome size (bp) | |||

| KJJ81 subgenome A | KJJ81 subgenome B | KPH12 | ATCC36309 | |||||

| KJJ81 | 38.6 | 12 185 | 14 | 67 516 | ||||

| KJJ81 subgenome A | 19.7 | NA | 7 | 100.0 | 89.0 | 99.1 | 97.9 | NA |

| KJJ81 subgenome B | 18.8 | NA | 7 | 89.0 | 100.0 | 88.6 | 90.0 | NA |

| KPH12 | 19.7 | 6 155 | 7 | 99.1 | 88.6 | 100.0 | 98.0 | 67 427 |

| ATCC36309 | 19.6 | NA | 7 | 97.9 | 90.0 | 98.0 | 100.0 | NA |

| Note:NA indicates data not available | ||||||||

|

| *在亚基因组B谱系中某些非必需基因的缺失可能发生在杂交事件之后 *Some non-essential genes in the subgenome B lineage could occur after a hybridization event 图 1 基于基因组序列分析推测的S.fibuligera杂合二倍体菌株KJJ81形成过程(仿自Choo等[11]) Fig. 1 Hybrid formation of S.fibuligera KJJ81 based on genome sequence analysis speculation (modified from Choo et al.[11]) |

部分只含有A型基因组的菌株和含有A、B型基因组的杂合菌株具有形态差异:前者的菌落呈白色或微红色,可通过菌丝吻合(Anastomosis)产生大量包含4个子囊孢子的子囊,而杂合菌株只呈现白色,产生较少的子囊[13]。在高温和硫限制条件下,杂合菌株表现出更强的适应性[11, 13]。

2 扣囊复膜酵母的产酶特性目前关于扣囊复膜酵母的研究多集中于它所分泌的胞外水解酶,包括β-葡糖苷酶、淀粉酶、蛋白酶等。这些酶绝大部分在葡萄糖或硫限制条件下可被诱导表达,且受Mig1负调控[11-12]。扣囊复膜酵母产生的水解酶可以分解大曲、酒醅中的大分子物质,为酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)等其他参与酿酒的微生物提供营养。

2.1 β-葡糖苷酶纤维素酶包括内切葡聚糖酶(EC 3.2.1.4)、外切葡聚糖酶(EC 3.2.1.91)和β-葡糖苷酶(EC 3.2.1.21)[14]。纤维素先经内/外切葡聚糖酶降解为纤维二糖和寡糖,再由β-葡糖苷酶降解为葡萄糖。β-葡糖苷酶为限速酶,可以解除纤维二糖对内/外切葡聚糖酶的抑制,从而决定纤维素的降解速度和程度[15-16]。

目前已从扣囊复膜酵母中分离得到两种β-葡糖苷酶:BGL1和BGL2,其蛋白序列高度相似(83%),在不同pH值、温度及热变性条件下具有相近的酶学特性,但BGL1可以更有效地降解纤维二糖[17]。BGL1可被Cr6+、Mn2+和Fe2+激活,其中Cr6+的激活效果最显著[18]。此外,还在菌株KPH12、KJJ81和ATCC36309的基因组中发现与BGL1基因具有一定同源性(55%)的BGL3,以及编码裂殖酵母β-葡糖苷酶的同系物基因BGL4,但其功能尚未得到验证[11]。

将扣囊复膜酵母的β-葡糖苷酶基因导入酿酒酵母S.cerevisiae菌株中可用于生产生物乙醇,包括将其整合到基因组中(如27rDNA区域)[19]或通过外源载体表达该基因。在优化外源载体表达条件时,发现利用组成型启动子(Actin Promoter)表达要优于诱导型启动子(Galactose-Inducible Promoter)[20]。分泌到胞外的β-葡糖苷酶在水解速率和乙醇产量上均优于胞内β-葡糖苷酶[21]。此外,乙醇产量与转化菌株的遗传背景也有相关性[20]。

2.2 酸性蛋白酶酸性蛋白酶,也称为天冬氨酸蛋白酶(EC 3.4.23),具有以天冬氨酸位点为催化中心的两个活性区域,特征序列分别为N端的Asp32-Thr-Gly-Ser和C端的Asp215-Thr-Gly-Ser/Thr[22]。酸性蛋白酶在白酒发酵中的作用包括:(1)溶解颗粒状原料并从颗粒上释放被吸附的α淀粉酶[23-24];(2)分解原料、死菌菌体蛋白生成的氨基酸, 供酿酒酵母摄取利用,促进酵母菌生长繁殖[23-24];(3)酵母中氨基酸合成的起始物多来自于糖代谢途径中间产物,吸收利用外源氨基酸可减少自身氨基酸合成代谢,使底物用于酒精发酵,提高出酒率[24-26];(4)氨基酸是白酒中高级醇的主要来源,而高级醇及其派生物是白酒中重要的呈香物质[24]。

扣囊复膜酵母中的酸性蛋白酶多为分泌型(Secreted Aspartyl Proteases,SAP),在N端有作为分泌信号的疏水片段,在基因组中常含有多个拷贝[11, 27]。扣囊复膜酵母中酸性蛋白酶的活性下降会增加海藻糖的积累量,提高淀粉酶的活性和稳定性[27]。

扣囊复膜酵母中酸性蛋白酶包括两类,一类为天冬氨酸蛋白酶PEP1(Aspartic Protease PEP1)类同源物[28-29],不含糖基磷脂酰肌醇(Glycosylphosphatidylinositol,GPI)锚定基序(Anchor Motif),这类酶在葡萄糖和硫限制条件下被诱导表达[11];另一类为酵母天冬氨酸蛋白酶Yapsin (Yeast Aspartic Protease)类同源物,在C端具有GPI锚定基序,帮助其定位于细胞壁表面,这类酶为组成型表达[11, 30]。

除了在白酒酿造过程中发挥作用,扣囊复膜酵母的酸性蛋白酶还可作为凝乳酶(Rennin),在奶酪制作等方面具有巨大潜力。凝乳酶可特异性水解牛奶中κ-酪蛋白内的Phe105-Met106间肽键,破坏酪蛋白胶束,从而使牛奶絮凝。Yu等[31]在解脂耶罗维亚酵母(Yarrowia lipolytica)菌株Po1h中克隆表达了S.fibuligera菌株A11的蛋白酶基因APG,筛选得到具有最大水解圈的转化子71;从转化子71培养基上清中纯化得到重组酶,其分子量约为94.8 kDa,最适pH值为3.5,最适温度为33℃;Zn2+可作为激活剂,而部分离子(Hg2+、Fe2+、Fe3+和Mg2+)、EDTA、EGTA、碘乙酸和胃蛋白酶抑制剂会抑制其酶活[31]。由于表面展示的酸性蛋白酶无需纯化,可直接应用于凝乳过程,节省了成本。Yu等[30]将APG基因克隆至表面展示载体(Surface Display Vector)pINA1317-YlCWP110并在Po1h中表达,发现重组蛋白的His标签会降低蛋白酶及凝乳酶活性。分离自海洋鱼类肠道的Y.lipolytica菌株SWJ-1b具有用作单细胞蛋白的潜力,为提高其凝乳酶活性,Yu等[32]先将原有的蛋白酶基因AXP敲除,以防止其降解外源蛋白,随后克隆表达了A11的酸性蛋白酶基因AP1,所得转化子43酶活力(46.7 U/mg)高于此前得到的菌株Po1h转化子71的酶活力(26.3 U/mg);转化子43中粗蛋白含量为43.53% (W:W),略低于原始菌株SWJ-1b(45.63%),但其凝乳酶活性优于原始菌株SWJ-1b,因此可用于生产凝乳酶,或作为食品工业中相应蛋白质的来源。

2.3 淀粉酶淀粉是由直链淀粉(由α-1, 4糖苷键连接D-葡萄糖残基而成)和支链淀粉(分别由α-1, 4和α-1, 6糖苷键连接D-葡萄糖残基而成)组成,可被淀粉酶降解为葡萄糖、寡糖和糊精[33]。目前对扣囊复膜酵母中淀粉酶的研究多集中于α-淀粉酶(EC 3.2.1.1)、葡糖淀粉酶(EC 3.2.1.3)和生淀粉糖化酶。

2.3.1 α-淀粉酶α-淀粉酶可催化水解淀粉中的α-1, 4糖苷键,与其他淀粉酶协同作用,可将淀粉分解为α-极限糊精、寡糖、麦芽糖和葡萄糖[34]。

目前已报道的扣囊复膜酵母α-淀粉酶包括ALP1[35-36]、Sfamy KZ[37]、Sfamy R64[38]和SFA1[39],其蛋白序列长度约为494个氨基酸,最适pH值为5.0-6.0,最适温度为40-50℃; 其蛋白N端与催化活性有关,C端与热稳定性及结合淀粉的能力有关[38]。扣囊复膜酵母α-淀粉酶可少量降解生淀粉并具有底物浓度依赖性,但不能结合在淀粉颗粒上[37-38]。

扣囊复膜酵母α-淀粉酶的C端缺少由芳香族氨基酸组成的表面结合位点[40],对其进行模拟改造(多个位点突变:S383Y/S386W/N421G/S278N/A281K/Q384K/K398R和引入环G400-S401)可提高其吸附淀粉的能力[40-41]。此外,利用化学修饰和点突变(S336C/S437C)也可提高α-淀粉酶的稳定性,保护辅助因子Ca2+,提高对胰蛋白酶的抗性[42-43]。在工业应用中,将扣囊复膜酵母α-淀粉酶基因与其他基因(S.cerevisiae谷氨酰半胱氨酸合成酶基因GSH1 [44],疏绵状嗜热丝孢菌(Thermomyces lanuginosus)葡糖淀粉酶基因TLG1 [45])组合导入酿酒酵母中,可用以生产啤酒或生物乙醇发酵。

2.3.2 葡糖淀粉酶葡糖淀粉酶可以从淀粉分子和α-1, 4糖苷键连接的麦芽寡糖非还原末端逐步水解释放β-葡萄糖[46],也可以低效水解α-1, 6糖苷键[47]。

目前已报道的扣囊复膜酵母葡糖淀粉酶包括GLU、GLA、GLL、GLM(表 2),此外也在部分菌株基因组中发现与白色念珠菌葡糖淀粉酶基因GAM1同源的开放阅读框(Open Reading Frame,ORF)[11]。

| Enzyme | Strains | Optimal pH | Optimal tempe- rature (℃) | Km (mmol/L) maltooligosacharide | Raw starch digestion | Amino acids of mature protein | Amino acids of signal peptide | Variant sites in the protein molecule | References | |||

| Malt- ose | Malto- triose | Maltote- traose | Maltohe- ptaose | |||||||||

| GLU | HUT7212 | 5.8 | 50 | 1.97 | 0.4 | 0.087 | 0.053 | No | 492 | 27 | E27, N46, E166, A377, A410, Y461, G467 | [48-53] |

| GLA | KZ | 5.0-6.2 | 40-50 | 1.82 | 0.33 | 0.081 | 0.05 | No | 492 | 27 | D27, D46, K166, V377, G410, N461, S467 | [46, 49-51, 53-54] |

| GLL | R64 | 5.6-6.4 | 50 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No | 492 | NA | D27, D46, E166, V377, A410, Y461, G467 | [49-50] |

| GLM | IFO 0111 | 4.8-5.0 | 40 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | 489 | 26 | NA | [49, 55-58] |

| Note:NA, data not available; Different colors indicate that variant sites in GLL are the combination of some variant sites in GLU and GLA | ||||||||||||

将GLU和GLA基因导入酿酒酵母表达,GLU酶活力高于GLA酶活力[46, 59]。两者信号肽及N端的变异对酶的表达水平没有影响,而C端的变异会同时影响酶活力、底物特异性、最适温度和最适pH值。糖基化程度不同会导致表达产物不均一,影响热稳定性以及热变性后的复性能力,但不影响酶活力[50, 59]。将GLU中C端保守活性区域S5中的Gly467替换为GLA中的Ser,会使其与底物的亲和性接近于GLA,酶的稳定性降低,但与底物类似物阿卡波糖的结合能力提高[50]。

菌株IFO 0111产生的单一淀粉酶GLM是目前唯一报道的,可以降解生淀粉的扣囊复膜酵母葡糖淀粉酶[56-57],而GLU、GLA和GLL只能较弱地吸附但不能降解生淀粉[51]。这是由于GLM中含有更多的色氨酸和组氨酸,其中的芳香族氨基酸(如色氨酸)可以通过疏水堆积作用与底物的糖环结合[51]。GLM可水解淀粉、糖原和极限糊精等多种多糖产生葡萄糖。GLM具有很高的脱支活性(Debranching Activity),对含支链底物(如支链淀粉、糖原和极限糊精)的降解程度很高,但不能彻底降解直链淀粉[60],其降解生淀粉的最适pH值为4.5,而降解可溶性淀粉的最适pH值为5.5。当pH值为2.0-7.6时,GLM可以完全吸附在生淀粉上;该酶催化生淀粉的活性会被淀粉酶抑制剂阻遏,但其对淀粉的吸附性不受影响[57]。

大部分葡糖淀粉酶是由淀粉催化区域和结合区域通过O-糖基化区域连接而成[61],但GLU和GLM都缺少独立的淀粉结合区域,它们在酶的活性位点附近有一些与生淀粉结合相关的氨基酸残基(GLM/GLU:D122/K121、H201/Y200、T204/S203、S205/T204、Q276/D277、S278/N282、S139/A138、E60/N60、V351/D354、T353/S356)[51]。在GLU表面距催化位点25 -处有另一个淀粉结合位点,该位点处的Arg15、His447、Asp450、Thr462、Tyr464和Ser465具有重要作用。将其中部分氨基酸(Arg15Ala、His447Ala、Thr462Ala和His447Ala/Asp450Ala)突变后,GLU不能再与生淀粉结合。在GLM中部分氨基酸也很保守(Arg15、His444、Asp447、Thr459和Phe461)[47],将GLM的His444和Asp447突变为Ala后,GLM结合生淀粉的能力下降,说明这一位点对结合生淀粉具有重要作用[62]。

3 扣囊复膜酵母对白酒风味物质的影响扣囊复膜酵母的代谢物对白酒香型、风味的形成具有一定作用,其代谢谱与菌株[63-65]、酶活力[66]、培养基成分[67]及培养时间[67]有关。当碳源为葡萄糖时,主要的挥发性代谢物包括2-苯乙醇、2-乙酸苯乙酯和苯乙酸乙酯,这些均为苯丙氨酸衍生物,呈果香或花香;主要的非挥发性代谢物包括3种碳水化合物(甘露糖、阿拉伯醇、甘露醇)、4种脂肪酸(丙酸、软脂酸、硬脂酸、肉豆蔻酸)、2种有机酸(草酸、琥珀酸)和8种氨基酸(异亮氨酸、丝氨酸、丙氨酸、谷氨酸、甘氨酸、脯氨酸、苯丙氨酸、苏氨酸)[67]。当培养基为高粱时,代谢物包括9种酯类、5种内酯类、7种醇类、9种萘酚类、7种酸类和4种醛酮类化合物,其中6种化合物(苯乙酸乙酯、乙酸苯乙酯、苯乙醛、4-乙基愈创木酚、3-甲基丁酸和苯乙酸)为牛栏山二锅头白酒的重要生香成分[63]。

在米根霉、酿酒酵母中加入扣囊复膜酵母混合发酵可提升酒中总酸和氨基态氮的含量,同时大幅减少酒中的有害醇(甲醇、异丁醇、异戊醇)和总高级醇的含量,从而改善酒的品质。推测其原因,可能是由于扣囊复膜酵母菌株无法将丙酮酸高效转化为乙醇,转而生成乳酸和乙酸等,间接抑制了高级醇的生成。除丁酸乙酯,其他酯类(乙酸乙酯、乳酸乙酯、己酸乙酯)和总低级酯在混合发酵中均有增加,使酒的风味得到改善[66]。

4 展望目前关于扣囊复膜酵母中的主要水解酶系和代谢谱已有大量研究,全基因组的公布也为进一步开发利用该物种提供了参考。鉴于扣囊复膜酵母的功能特性,未来还可通过对组学数据的进一步分析和分子生物学研究,阐明其在白酒发酵过程中的代谢通路调控,以及与其他白酒微生物的互作关系。此外,还需确定不同风味白酒酿造中适应不同工艺和发酵条件的扣囊复膜酵母菌株遗传多样性及其在生理、功能上的差异,从而为实际生产中筛选优良菌株,改良白酒品质提供参考依据。

| [1] |

KURTZMAN C P.Chapter 13: Discussion of teleomorphic and anamorphic ascomycetous yeasts and yeast-like Taxa[M]//KURTZMAN C P, FELL J W, BOEKHOUT T.The yeasts, a taxonomic study.Fifth Edition.Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2011: 293-307.

|

| [2] |

KURTZMAN C P, SMITH M T.Chapter 63: Saccharomycopsis Schiönning (1903)[M]//KURTZMAN C P, FELL J W, BOEKHOUT T.The yeasts, a taxonomic study.Fifth Edition.Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2011: 751-763.

|

| [3] |

WICKERHAM L J, LOCKWOOD L B, PETTIJOHN O G, et al. Starch hydrolysis and fermentation by the yeast Endomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 1944, 48(4): 413-427. |

| [4] |

JUNG M J, NAM Y D, ROH S W, et al. Unexpected convergence of fungal and bacterial communities during fermentation of traditional Korean alcoholic beverages inoculated with various natural starters[J]. Food Microbiology, 2012, 30(1): 112-123. |

| [5] |

LIMTONG S, SINTARA S, SUWANNARIT P, et al. Yeast diversity in Thai traditional alcoholic starter[J]. Kasetsart J (Nat Sci), 2002, 36: 149-158. |

| [6] |

LV X C, HUANG X L, ZHANG W, et al. Yeast diversity of traditional alcohol fermentation starters for Hong Qu glutinous rice wine brewing, revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods[J]. Food Control, 2013, 34(1): 183-190. |

| [7] |

ZHENG X W, YAN Z, ROBERT NOUT M J, et al. Characterization of the microbial community in different types of Daqu samples as revealed by 16S rRNA and 26S rRNA gene clone libraries[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 31(1): 199-208. |

| [8] |

ZHENG X W, YAN Z, ROBERT NOUT M J R, et al. Microbiota dynamics related to environmental conditions during the fermentative production of Fen-Daqu, a Chinese industrial fermentation starter[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 182/183: 57-62. |

| [9] |

朱婷婷. 牛栏山大曲可培养微生物多样性分析[J]. 酿酒科技, 2018(5): 75-79. |

| [10] |

周森, 韩培杰, 胡佳音, 等. 牛栏山二锅头酿造过程中的真菌多样性分析[J]. 食品工业科技, 2018, 39(1): 127-130, 136. |

| [11] |

CHOO J H, HONG C P, LIM J Y, et al. Whole-genome de novo sequencing, combined with RNA-Seq analysis, reveals unique genome and physiological features of the amylolytic yeast Saccharomycopsis fibuligera and its interspecies hybrid[J]. Biotechnol Biofuels, 2016, 9(1): 246-267. |

| [12] |

LIU G L, WANG D S, WANG L F, et al. Mig1 is involved in mycelial formation and expression of the genes encoding extracellular enzymes in Saccharomycopsis fibuligera A11[J]. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 2011, 48(9): 904-913. |

| [13] |

FARH M E, CHO Y, LIM J Y, et al. A diversity study of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera in rice wine starter nuruk, reveals the evolutionary process associated with its interspecies hybrid[J]. The Journal of Microbiology, 2017, 55(5): 337-343. |

| [14] |

GUO Z P, ZHANG L, DING Z Y, et al. Development of an industrial ethanol-producing yeast strain for efficient utilization of cellobiose[J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2011, 49(1): 105-112. |

| [15] |

SINGHANIA R R, PATEL A, PANDEY A, et al. Genetic modification:A tool for enhancing beta-glucosidase production for biofuel application[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 245: 1352-1361. |

| [16] |

WILDE C, GOLD N D, BAWA N, et al. Expression of a library of fungal β-glucosidases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the development of a biomass fermenting strain[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2012, 95(3): 647-659. |

| [17] |

MACHIDA M, OHTSUKI I, FUKUI S, et al. Nucleotide sequences of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera genes for extracellular beta-glucosidases as expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1988, 54(12): 3147-3155. |

| [18] |

MA Y Y, LIU X W, YIN Y C, et al. Expression optimization and biochemical properties of two glycosyl hydrolase family 3 beta-glucosidases[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2015, 206: 79-88. |

| [19] |

SHEN Y, ZHANG Y, MA T, et al. Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of acid-pretreated corncobs with a recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing β-glucosidase[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2008, 99(11): 5099-5103. |

| [20] |

GURGU L, LAFRAYA Á, POLAINA J, et al. Fermen-tation of cellobiose to ethanol by industrial Saccharomyces strains carrying the β-glucosidase gene(BGL1) from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2011, 102(8): 5229-5236. |

| [21] |

CASA-VILLEGAS M, POLAINA J, MARIN-NAVA-RRO J. Cellobiose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae:Comparative analysis of intra versus extracellular sugar hydrolysis[J]. Process Biochemistry, 2018, 75: 59-67. |

| [22] |

DAVIES D R. The structure and function of the aspartic proteinases[J]. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem, 1990, 19(1): 189-215. |

| [23] |

周恒刚. 白酒生产与酸性蛋白酶[J]. 酿酒, 1991(6): 5-8. |

| [24] |

周恒刚. 酸性蛋白酶在酿酒上的功用[J]. 酿酒科技, 1998(6): 7. |

| [25] |

赵华, 赵树欣, 张维, 等. 酒精发酵中应用酸性蛋白酶的研究[J]. 食品与发酵工业, 1997, 23(2): 26-28. |

| [26] |

王彦荣, 孟祥春, 任连彬, 等. 酸性蛋白酶生产与应用的研究[J]. 酿酒, 2003, 30(3): 16-18. |

| [27] |

WANG D S, CHI Z, ZHAO S F, et al. Disruption of the acid protease gene in Saccharomycopsis fibuligera A11 enhances amylolytic activity and stability as well as trehalose accumulation[J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2011, 49(1): 88-93. |

| [28] |

HIRATA D, FUKUI S, YAMASHITA I. Nucleotide sequence of the secretable acid protease genePEP1 in the yeast Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1988, 52(10): 2647-2649. |

| [29] |

YAMASHITA I, HIRATA D, MACHIDA M, et al. Cloning and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of the secretable acid protease gene from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1986, 50(1): 109-113. |

| [30] |

YU X J, MADZAK C, LI H J, et al. Surface display of acid protease on the cells of Yarrowia lipolytica for milk clotting[J]. Applied Microbiology & Biotechnology, 2010, 87(2): 669-677. |

| [31] |

YU X J, LI H J, LI J, et al. Overexpression of acid protease of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera in Yarrowia lipolytica and characterization of the recombinant acid protease for skimmed milk clotting[J]. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, 2010, 15(3): 467-475. |

| [32] |

YU X J, CHI Z, WANG F, et al. Expression of the acid protease gene from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera in the marine-derived Yarrowia lipolytica for both milk clotting and single cell protein production[J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2013, 169(7): 1993-2003. |

| [33] |

KNOX A M, DU PREEZ J C D, KILIAN S G. Starch fermentation characteristics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains transformed with amylase genes from Lipomyces kononenkoae and Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2004, 34(5): 453-460. |

| [34] |

CHI Z M, CHI Z, LIU G L, et al. Saccharomycopsis fibuligera and its applications in biotechnology[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2009, 27(4): 423-431. |

| [35] |

ITOH T, YAMASHITA I, FUKUI S. Nucleotide sequence of the α-amylase gene(ALP1)in the yeast Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. FEBS Letters, 1987, 219(2): 339-342. |

| [36] |

YAMASHITA I, ITOH T, FUKUI S, et al. Cloning and expression of the Saccharomycopsis fibuligera α-amylase gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1985, 49(10): 3089-3091. |

| [37] |

HOSTINOVÁ E, JANEČEK Š, GAŠPERÍK J. Gene sequence, bioinformatics and enzymatic characterization of α-amylase from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera KZ[J]. The Protein Journal, 2010, 29(5): 355-364. |

| [38] |

HASAN K, ISMAYA W T, KARDI I, et al. Proteolysis of α-amylase from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera:Characterization of digestion products[J]. Biologia, 2008, 63(6): 1044-1050. |

| [39] |

EKSTEEN J M, VAN RENSBURG P, CORDERO OTERO R R, et al. Starch fermentation by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains expressing the α-amylase and glucoamylase genes from Lipomyces kononenkoae and Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2003, 84(6): 639-646. |

| [40] |

YUSUF M, BAROROH U, HASAN K, et al. Computational model of the effect of a surface-binding site on the Saccharomycopsis fibuligera R64α-amylase to the substrate adsorption[J]. Bioinformatics and Biology Insights, 2017, 11: 1-8. DOI:10.1177/1177932217738764 |

| [41] |

BAROROH U, YUSUF M, RACHMAN S D, et al. Molecular dynamics study to improve the substrate adsorption of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera R64 alpha-amylase by designing a new surface binding site[J]. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem, 2019, 12: 1-13. |

| [42] |

ISMAYA W T, HASAN K, KARDI I, et al. Chemical modification of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera R64α-amylase to improve its stability against thermal, chelator, and proteolytic inactivation[J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2013, 170(1): 44-57. |

| [43] |

NATALIA D, VIDILASERIS K, ISMAYA W T, et al. Effect of introducing a disulphide bond between the A and C domains on the activity and stability of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera R64α-amylase[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2015, 195: 8-14. |

| [44] |

WANG J J, WANG Z Y, HE X P, et al. Construction of amylolytic industrial brewing yeast strain with high glutathione content for manufacturing beer with improved anti-staling capability and flavor[J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2010, 20(11): 1539-1545. |

| [45] |

FAVARO L, VIKTOR M J, ROSE S H, et al. Consolidated bioprocessing of starchy substrates into ethanol by industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains secreting fungal amylases[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2015, 112(9): 1751-1760. |

| [46] |

HOSTINOVÁ E, BALANOVÁ J, GAŠPERÍK J. The nucleotide sequence of the glucoamylase gene GLA1 from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera KZ[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 1991, 67(1): 103-108. |

| [47] |

ŠEVČÍK J, HOSTINOVÁ E, SOLOVICOVÁ A, et al. Structure of the complex of a yeast glucoamylase with acarbose reveals the presence of a raw starch binding site on the catalytic domain[J]. FEBS Journal, 2006, 273(10): 2161-2171. |

| [48] |

YAMASHITA I, ITOH T, FUKUI S. Cloning and expression of the Saccharomycopsis fibuligera glucoamylase gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 1985, 23(2): 130-133. |

| [49] |

NATALIA D, VIDILASERIS K, SATRIMAFITRAH P, et al. Biochemical characterization of a glucoamylase from Saccharomycopsis fibuligera R64[J]. Biologia, 2011, 66(1): 27-32. |

| [50] |

SOLOVICOVÁ A, CHRISTENSEN T, HOSTINOVÁ E, et al. Structure-function relationships in glucoamylases encoded by variant Saccharomycopsis fibuligera genes[J]. Febs Journal, 1999, 264(3): 756-764. |

| [51] |

HOSTINOVÁ E, SOLOVICOVÁ A, DVORSKY R, et al. Molecular cloning and 3D structure prediction of the first raw-starch-degrading glucoamylase without a separate starch-binding domain[J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2003, 411(2): 189-195. |

| [52] |

ITOH T, OHTSUKI I, YAMASHITA I, et al. Nucleotide sequence of the glucoamylase geneGLU1in the yeast Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 1987, 169(9): 4171-4176. |

| [53] |

HOSTINOVÁ E, GAŠPERÍK J. Yeast glucoamylases:Molecular-genetic and structural characterization[J]. Biologia(Bratislava), 2010, 65(4): 559-568. |

| [54] |

GAŠPERÍK J, KOVÁČ L, MINÁRIKOVÁ O. Purification and characterization of the amylolytic enzymes of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. International Journal of Biochemistry, 1991, 23(1): 21-25. |

| [55] |

HATTORI Y. Studies on amylolytic enzymes produced by Endomyces sp.Part Ⅰ.Production of extracellular emylase by Endomyces sp.[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1961, 25(10): 737-743. |

| [56] |

HATTORI Y, TAKEUCHI I. Studies on amylolytic enzymes produced by Endomyces sp.Part Ⅱ.Purification and general propertiies of amyloglucosidase[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1961, 25(12): 895-901. |

| [57] |

UEDA S, SAHA B C. Behavior of Endomycopsis fibuligera glucoamylase towards raw starch[J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 1983, 5(3): 196-198. |

| [58] |

HOSTINOVÁ E. Amylolytic enzymes produced by the yeast Saccharomycopsis fibuligera[J]. Biologia, 2002, 57(11): 247-252. |

| [59] |

GAŠPERÍK J, HOSTINOVÁ E. Glucoamylases encoded by variant Saccharomycopsis fibuligera genes:Structure and properties[J]. Current Microbiology, 1993, 27(1): 11-14. |

| [60] |

HATTORI Y, TAKEUCHI I. Studies on amylolytic enzymes produced by Endomyces sp.Part Ⅲ. Hydrolysis of starch and glucosyl saccharides with amyloglucosidase[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1962, 26(5): 316-322. |

| [61] |

SAUER J, SIGURSKJOLD B W, CHRISTENSEN U, et al. Glucoamylase:Structure/function relationships, and protein engineering[J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 2000, 1543(2): 275-293. |

| [62] |

GAŠPERÍK J, HOSTINOVÁ E, ŠEVČÍK J. Acarbose binding at the surface of Saccharomycopsis fibuligera glucoamylase suggests the presence of a raw starch-binding site[J]. Biologia, 2005, 60. |

| [63] |

郝文军, 刘红霞, 于晓涛, 等. 牛栏山白酒酿造过程中扣囊复膜酵母的分离与产物分析[J]. 酿酒科技, 2019, 296(2): 40-43. |

| [64] |

王琨, 伍时华, 赵东玲, 等. 扣囊复膜酵母复合菌株对糯米酒风味物质的影响[J]. 酿酒, 2015, 42(2): 28-33. |

| [65] |

杨子琳, 伍时华, 黄翠姬, 等. 扣囊复膜酵母与酿酒酵母混合液态发酵改善糯米酒风味的研究[J]. 广西科技大学学报, 2016, 27(3): 95-100. |

| [66] |

SON E Y, LEE S M, KIM M, et al. Comparison of volatile and non-volatile metabolites in rice wine fermented by Koji inoculated with Saccharomycopsis fibuligera and Aspergillus oryzae[J]. Food Research International, 2018, 109: 596-605. |

| [67] |

LEE S M, JUNG J H, SEO J A, et al. Bioformation of volatile and nonvolatile metabolites by Saccharomycopsis fibuligera KJJ81 cultivated under different conditions-carbon sources and cultivation times[J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(11): 2762. |